View life with a different perspective.

Don’t be reliant on what you have always done, and don’t be afraid to try something new.

Just because the world is colour, it doesn’t mean you can’t see in black and white.

View life with a different perspective.

Don’t be reliant on what you have always done, and don’t be afraid to try something new.

Just because the world is colour, it doesn’t mean you can’t see in black and white.

Find someone to share your day with.

Talk to a family member, email a distant friend, text a colleague.

Share what you have done, but ask them how their day has been.

Value the friendships you have formed over the years.

They are the bond that keep you sane, bring you joy and give you a a sense of community.

Don’t take your friends for granted; they will see you through the dark times, and you can help them through theirs.

Don your finery and deliver what you you want others to see.

Clothes can make you shine brightly, or make you invisible, and emotions can do the same.

In times of extreme stress a brave face may be needed, but you don’t have to conceal what is on the inside to everyone around you.

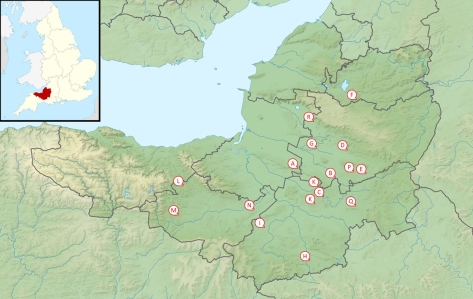

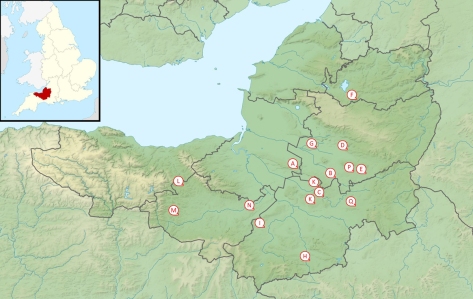

At the foothills of the Mendips, on the main road between Wells and Weston-super-Mare, lies the quiet, unassuming village of Rodney Stoke. Owned by a number of families over the years, Stoches (old English for ‘settlement’) has been known as Stoke Whiting, Stoke Giffard and Stoke Rodney over the years, before the name settled on Rodney Stoke.

With a population of close to 1,500 people, you would expect the village to be a bustling affair, but settled as it is – along three lanes leading downhill from the A371 – it has an altogether quieter feel about it.

The lanes are lined with cottages built for former farm workers. Some former outbuildings have been converted into newer residences while other parts of the village are much newer properties, albeit still in keeping with the history of the village.

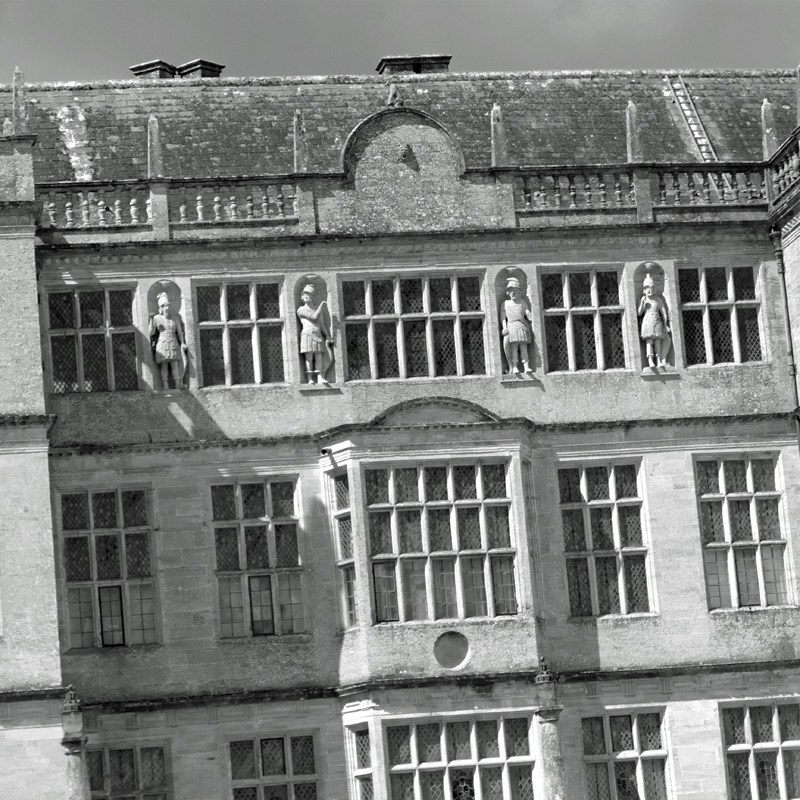

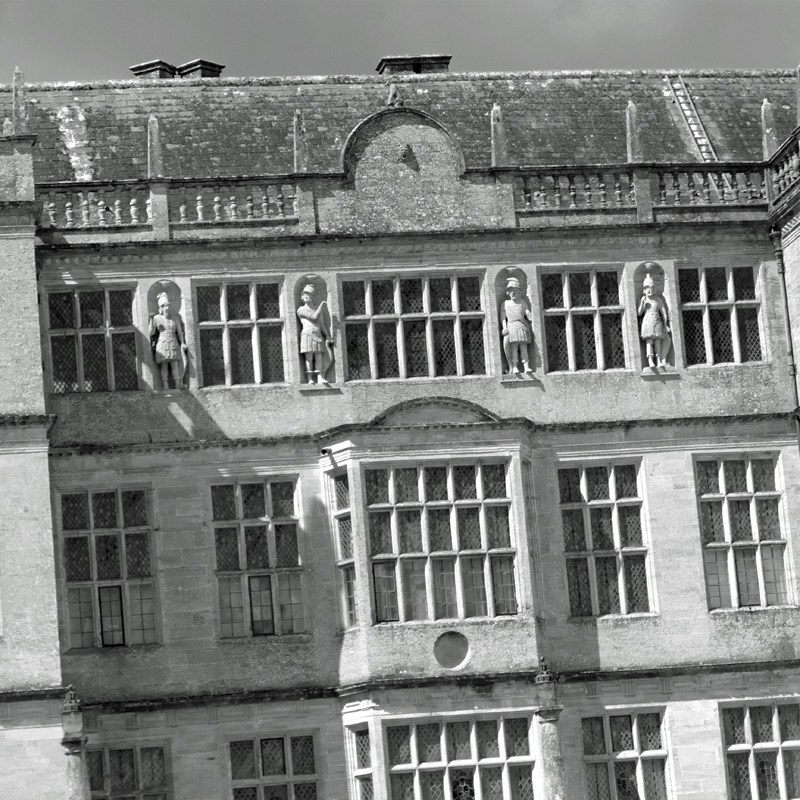

At the bottom of Stoke Street lies a farm, while the former manor house stands proud above the surrounding fields.

The parish church – St Leonard’s – is, unsurprisingly, place next to the manor house and, while hidden from most of the village, it can be clearly seen on the skyline from the south, standing tall and proud against the dramatic escarpment of the Mendips.

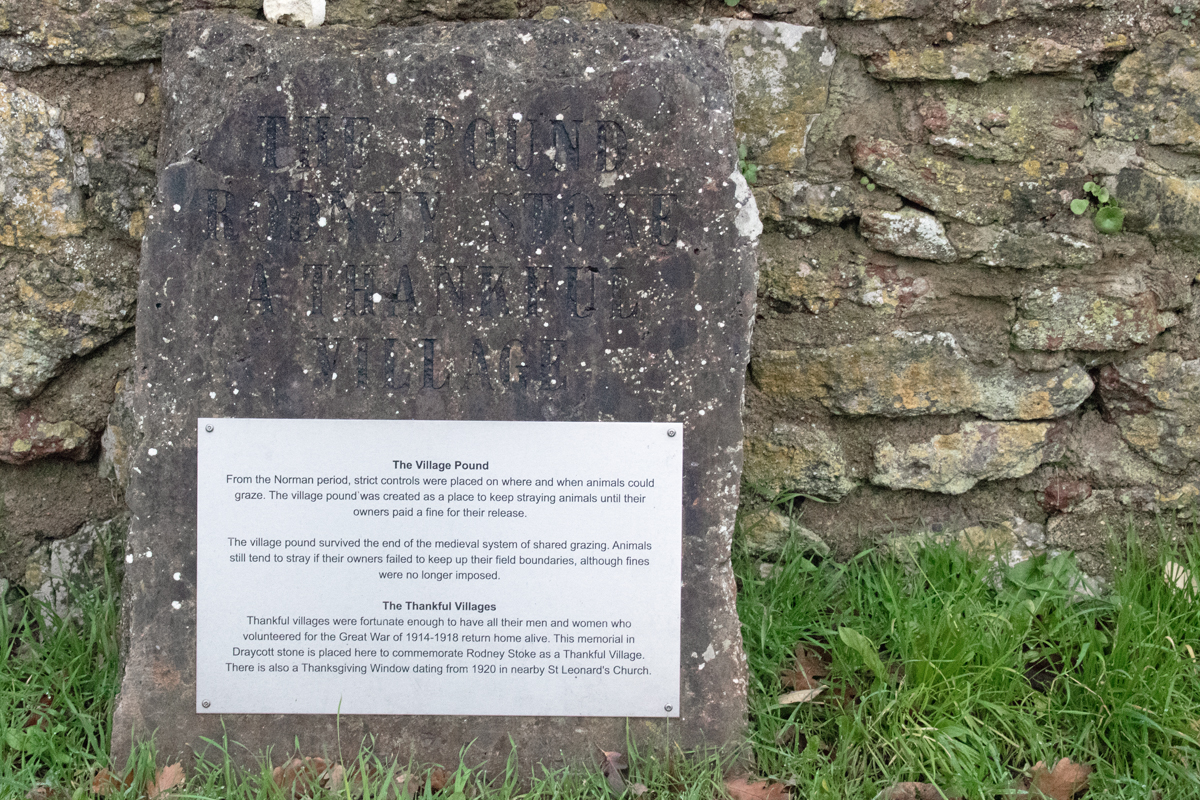

Normally, when I visit the local villages, I spent time in the churchyard looking for Commonwealth War Graves. However, Rodney Stoke stands out as one of the county’s Thankful Villages.

Fifty-three parishes in England and Wales are commemorated as having sent servicemen to war between 1914 and 1918, all of whom returned at the end of the conflict. These Thankful Villages stand out, particularly given that there are tens of thousands of towns and villages across the country.

Somerset has the highest number of Thankful Villages by county, with Rodney Stoke counting as one of nine. This is celebrated by a window in the church, giving thanks that “All glory be to God, whom in his tender mercy has brought again to their homes, the men and women of Rodney Stoke who took part in the Great War 1914-1919”.

(As an aside, Rodney Stoke sadly doesn’t fit into the category of being Doubly Thankful, having seen all of their service men and women return from both world wars. Four local residents – David Cooper, John Glover-Price, Denis Thayer and James Williams – perished in the 1939-1945 conflict.)

A second memorial to Rodney Stoke being thankful is situated in the Village Pound.

Since Norman times, strict controls were in place about where and when animals could graze on common land. The Pound – a walled area on the main road – was a place for straying animals to be kept until their owners paid the due fine.

As with other villages I have visited for this alphabetical journey, Rodney Stoke is definitely worth stopping by for. To the north of the village lie the Stoke and Stoke Woods Nature Reserves , and the village pub – the Rodney Stoke Inn – must also be worth a visit!

We live our lives based on what went before; and this can lead to what we have done before happening again.

While your roots are important, you need to ensure that you don’t repeat the same mistakes again.

Take a step back, identify objectively what worked and what didn’t, and try a new approach.

While dark clouds swirl around us, there is always light to be found.

It may not always be from the most obvious or conventional of sources, but it is there.

Find that chink in the darkness and follow it into the light.

Seven miles to the north of Yeovil, lies the unusually-named village of Queen Camel. While it sits on the main A359 road, this thoroughfare dog-legs through the village, so it avoids the speeding traffic of which Othery is a victim.

The name derives from the old English word cam, meaning ‘bare rim of hills’, a word shared by the river that runs through the village. The manor of Camel was given to the crown in the late 13th century, and the name was changed to Camel Regis (“King’s Camel”). Edward I gave the area to his wife, Eleanor, and so the name Queen Camel was born.

One of the highlights of the village is Church Path, a cobbled road that leads from the centre of Queen Camel to St Barnabas’ Church.

The church itself dates from the 1300s, and, despite the main road, is surrounded by a quiet churchyard and allotments. Additional architectural elements – including an imposing porch on the south side – were added in the 19th century, as part of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebrations.

The churchyard includes a gravestone to Seaman Donald Burgess, who died in the Great War, aged just 17 years old.

Details of his life can be found on the CKPonderingsCWG site, which is dedicated to those who lost their lives as a result of that conflict.

The houses in the village are all local stone, and while some are from the early 2000s, they fit in almost seamlessly with the old structures around them.

The Mildmay Arms is the village pub; again, it is reminiscent of a coaching inn, and was likely used as such at some point in its history.

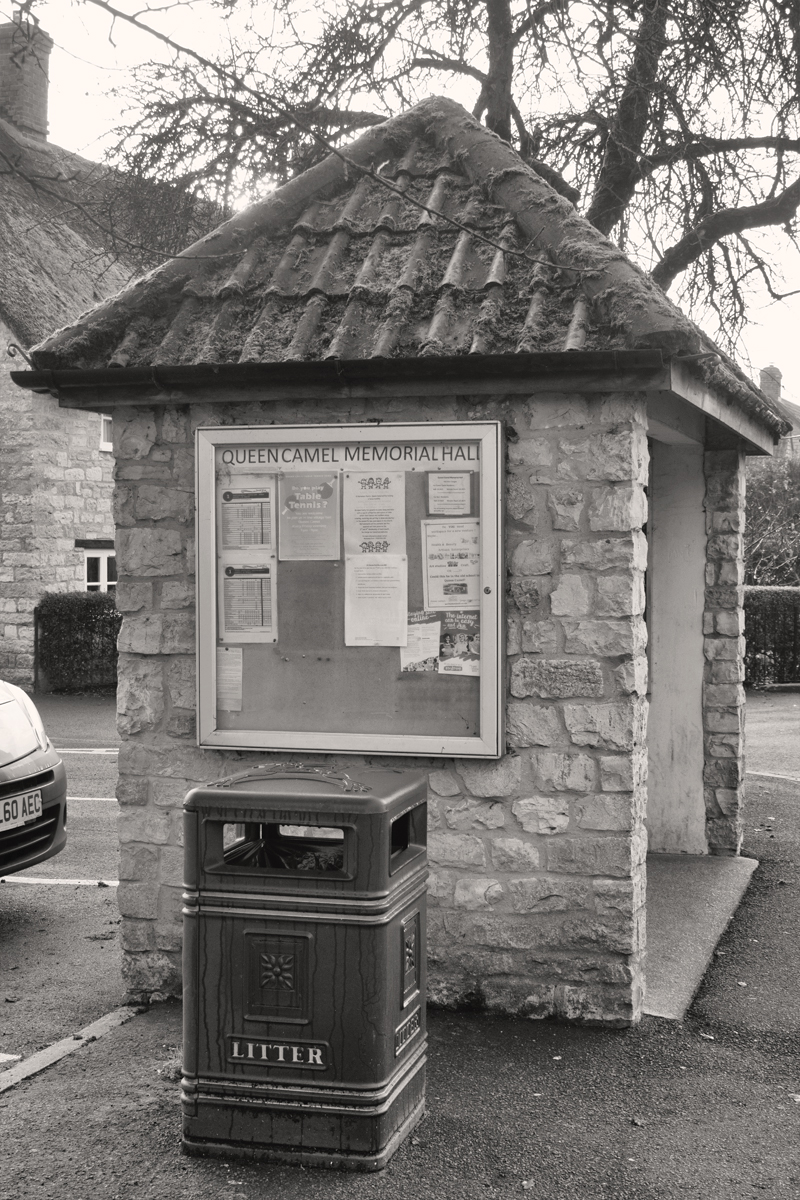

Queen Camel has an undoubted village feel; with a population of less than 1000 people, there is a definite sense of community here.

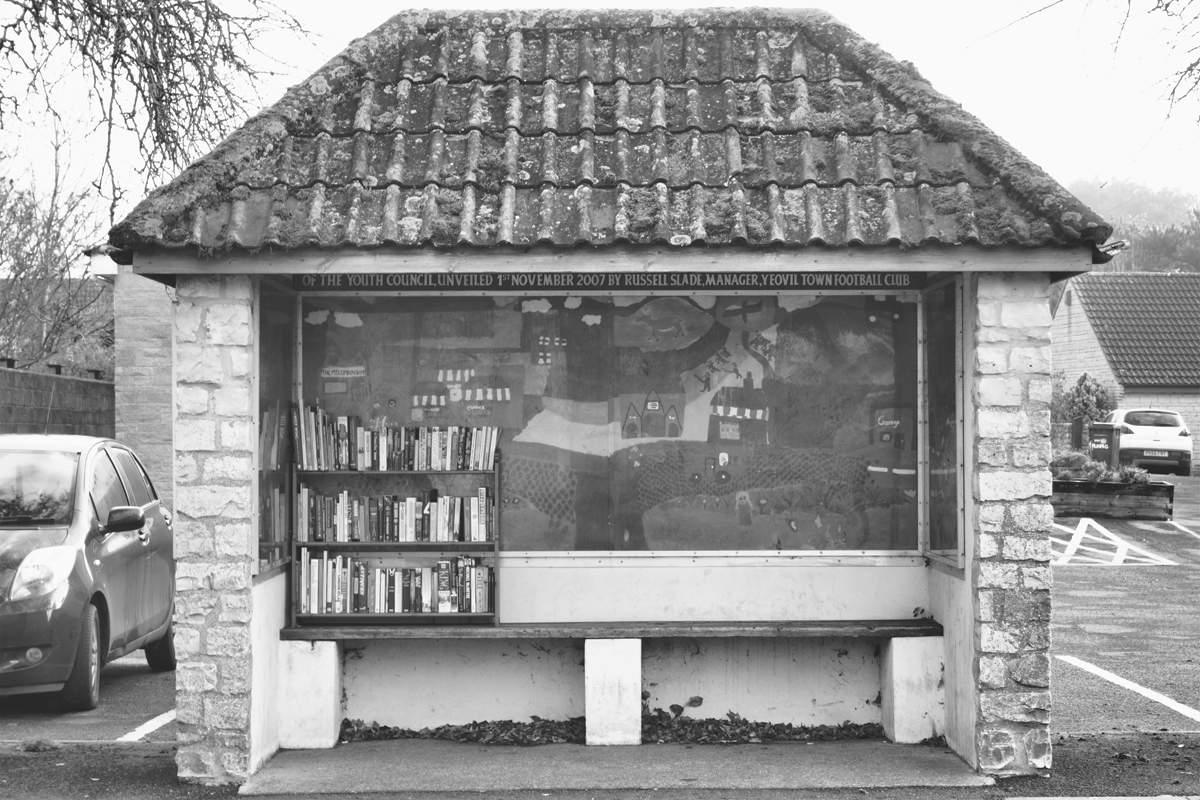

A former bus stop – standing outside the Memorial Hall – now houses a mural dedicated to the village’s history, as well as a book swap station.

There is a lane in Queen Camel that is dedicated to a Grace Martin; I have not been able to find out much about her. There is someone by that name – the daughter of John and Judith Martin – baptised in St Barnabas’ Church in July 1744. Beyond that she remains a mystery.

Despite its location, Queen Camel is a peaceful place to visit; a lovely addition to the Somerset A to Z.

Continue up the A361 for 16 miles from Othery and you reach the surprising village of Pilton. I have driven through the village countless times over the years, and there is so much more to it than what is visible from the main road.

Situated on the top of a hill to the east on Glastonbury, the village once overlooked an inland sea that stretched to the present day Bristol Channel. This lead to the village’s original name, Pooltown, because ships were able to navigate this far inland.

The houses in the village are old, from local stone, and really fit in with the country feel. Despite the main road, laden with juggernauts, being close by, the majority of the village is in a sheltered valley, and within a matter of metres away from the A361, it can barely be heard.

The local church is St John the Baptist, which is on the north side of the valley, has a commanding view across all Pilton. Once again, the Church’s dominance is in plain sight, and it can be seen on the skyline from most of the houses.

In the churchyard is a memorial, a grave to Sapper Percy Wright Rodgers, who fell in the First World War. More information on this young man’s life can be found on the CKPonderingsCWG blog, along with more stories of the fallen of the Great War.

To the south of the village, a tithe barn stands alone and proud. Once belonging to Glastonbury Abbey, the barn once stored local farmers’ produce, of which they gave the Abbey – the landowner – one tenth.

The barn is now a Grade 1 listed building.

In the barn’s grounds is a monument to the Land Armies of both world wars; a bench in a quiet corner of an already quiet corner of the village is perfect for contemplation.

When I first made my intention of moving to Somerset known to friend, family and colleagues, the general first reaction was usually related to the annual music festival. My stock response to this was ‘no’, and, if the mood was right, this was usually followed up by the fact that the Glastonbury Festival does not actually take place in the town of the same name.

Worthy Farm, the location of the festival, is situated just to the south of Pilton, six miles from Glastonbury. It was only called Glastonbury Festival because that was the nearest town people had heard of.

If you get the chance to make a quick pitstop from your journey to the south west, Pilton is definitely worth a visit. A genuine gem of a village, hidden in plain sight, it is also a good start and end point for a wander across the Levels or over the hilltops to Shepton Mallet.

As history moves on, it seems there were two main routes for villages to take. As we have seen, the first is to thrive, then to settle quietly into the background and become a quintessential English village, as with Haselbury Plucknett and Milverton (see previous posts).

The second option is not as positive, and this has been the route taken by the next village on our Somerset journey, Othery.

Sitting on the crossroads of the main roads between Bridgewater and Langport, Glastonbury/Street and Taunton, Othery once thrived as a stopping off point on the long journeys across sometimes threatening terrain.

The Other Island sits 82ft (20m) above the surrounding moorland of the River Parrett, and so proved a good resting point for horses, carriages and passengers alike. For a population of around 500 people, this was once a bustling place, boasting three pubs, a post office, village store and bakery.

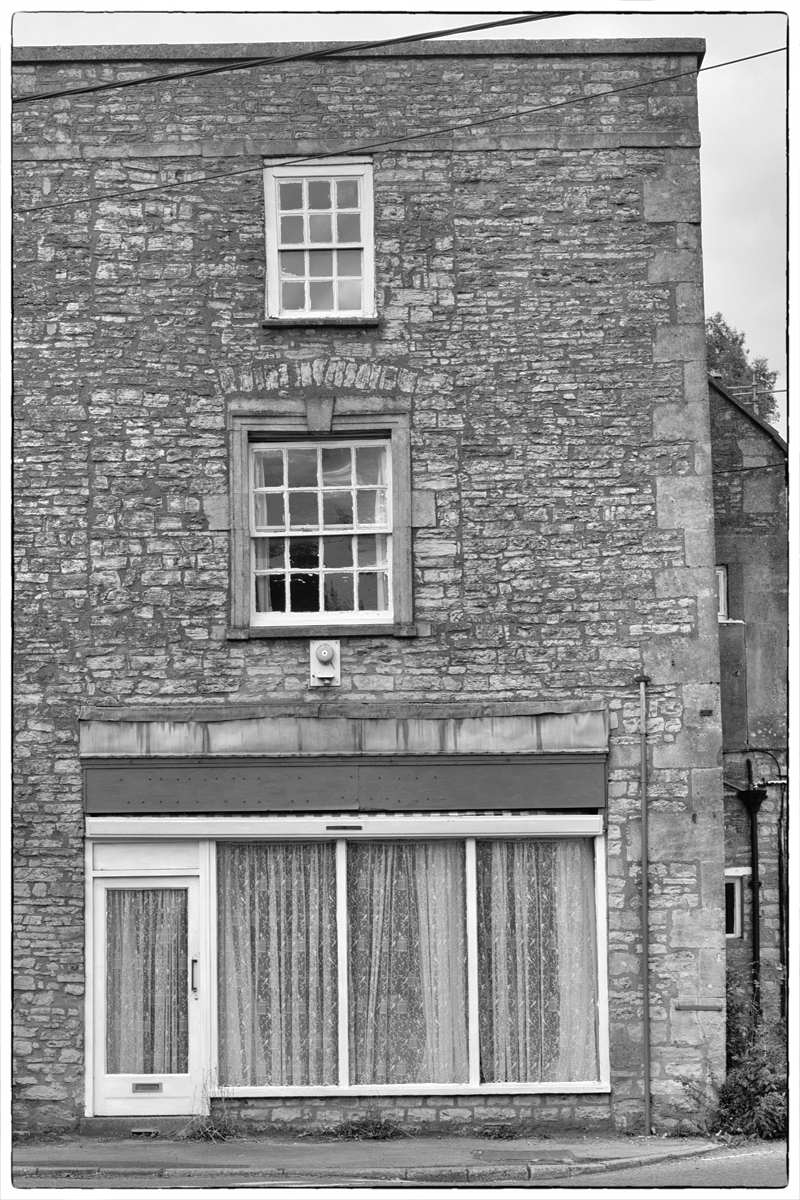

Sadly, the village has not thrived, and is nowadays more of a cut through, one of those places you see the road sign for, before slowing to 30mph and impatiently waiting for the national speed limit sign to come into view.

The buildings on the main road seem a little tired, once white frontages sullied by the dirt and grime of passing juggernauts. The signs outside the one remaining public house – the London Inn – almost beg you to stop, whether for a Sunday carvery or to watch weekend football matches on the huge TV screens.

(I admit the scaffolding does little to show the pub in its best light.)

But the fact of the matter is that, where once it would have had regular bookings, you can’t help feeling that this is very much a locals’ pub, whose inhabitants have set places at the bar and engraved tankards.

One glimmer of hope is that the the bakery seems to attract a lot of support. Again, it was closed when I stopped off here late one afternoon, but whenever I have driven through Othery before, there has tended to be a queue of people outside, and this gives a hint at a sense of community that the commuter doesn’t get to see.

The community sense continues with the school sign too; a typical redbrick Victorian building enticing children in. Another sign of things changing is that, where this was once Othery Village School, it has now merged with neighbouring Middlezoy; families move out of the smaller villages, school numbers drop, changes take place to help support struggling services.

Move away from the main road, though, and you can see tantalising hints of what Othery once was, and probably still would be, had its position on the crossroads not been the main function of its existence.

North Lane is a much quieter affair than the main road. In between the mid-20th Century houses sit more stately structures, hidden behind high walls to shelter them from passing traffic.

St Michael’s Church stands proud above the village, helping direct the wayward and lost to a better life. You get the feeling, however, that locals stay behind their high walls more than they used to, something sadly echoed across rural Britain more than one might care to admit.

I am painting a pretty bleak picture, I know, but, while not deliberately doing the village down, this is the sense you get when exploring a place like Othery.

Where villages like North Curry once had glory, they were fortunate in their locale. Those villages that lie too short a distance from neighbouring towns have struggled in recent years, and Othery is not an exception.

Using the same stretch of road between Street and Taunton as an example, places like Walton, Greinton, Greylake, East Lyng, West Lyng and Durston have also struggled over the years.

Villages with a distinct pull, a unique selling point, like Burrowbridge on the same stretch of road, do survive, but for others it has been a struggle.

Additional housing projects have tried to rejuvenate them, but without the infrastructure to support them, the villages still die or get swallowed up by those neighbouring towns.

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....