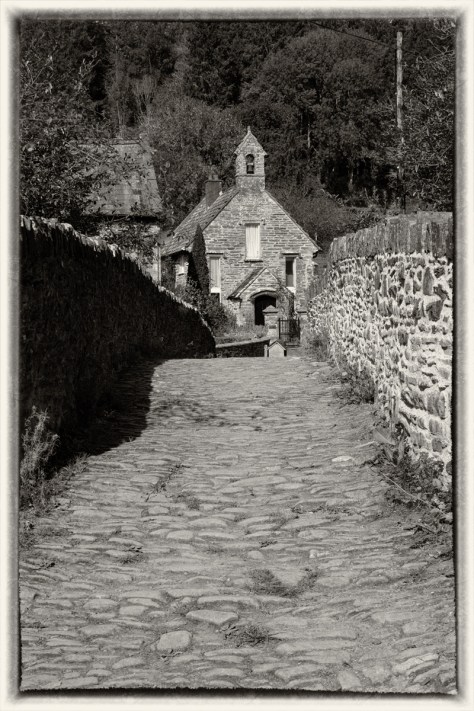

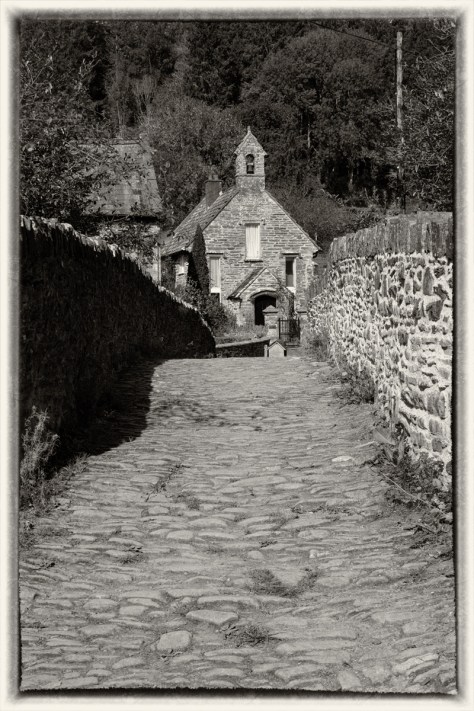

We rarely know for certain where the path ahead will take us.

There may be bumps along the way but these harden us to the journey ahead.

Adventures lie in front of us, and the mystery is all part of that road.

We rarely know for certain where the path ahead will take us.

There may be bumps along the way but these harden us to the journey ahead.

Adventures lie in front of us, and the mystery is all part of that road.

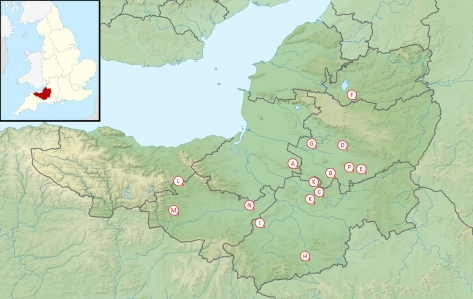

Continue up the A361 for 16 miles from Othery and you reach the surprising village of Pilton. I have driven through the village countless times over the years, and there is so much more to it than what is visible from the main road.

Situated on the top of a hill to the east on Glastonbury, the village once overlooked an inland sea that stretched to the present day Bristol Channel. This lead to the village’s original name, Pooltown, because ships were able to navigate this far inland.

The houses in the village are old, from local stone, and really fit in with the country feel. Despite the main road, laden with juggernauts, being close by, the majority of the village is in a sheltered valley, and within a matter of metres away from the A361, it can barely be heard.

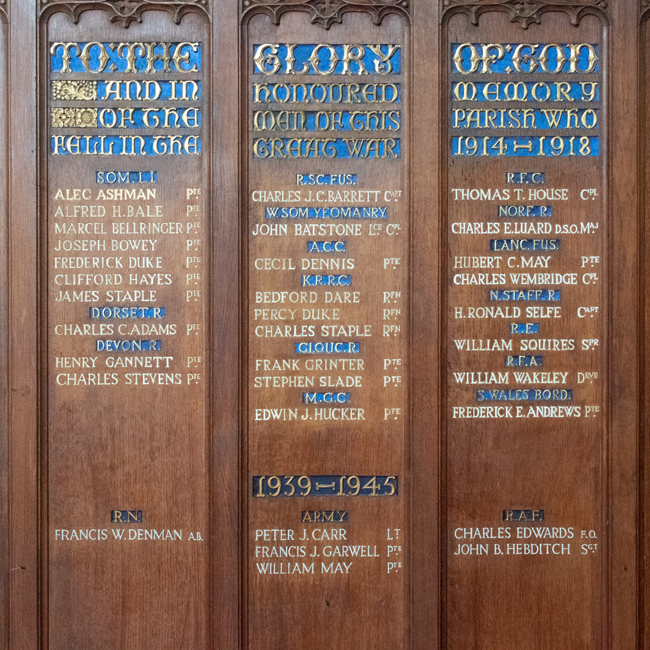

The local church is St John the Baptist, which is on the north side of the valley, has a commanding view across all Pilton. Once again, the Church’s dominance is in plain sight, and it can be seen on the skyline from most of the houses.

In the churchyard is a memorial, a grave to Sapper Percy Wright Rodgers, who fell in the First World War. More information on this young man’s life can be found on the CKPonderingsCWG blog, along with more stories of the fallen of the Great War.

To the south of the village, a tithe barn stands alone and proud. Once belonging to Glastonbury Abbey, the barn once stored local farmers’ produce, of which they gave the Abbey – the landowner – one tenth.

The barn is now a Grade 1 listed building.

In the barn’s grounds is a monument to the Land Armies of both world wars; a bench in a quiet corner of an already quiet corner of the village is perfect for contemplation.

When I first made my intention of moving to Somerset known to friend, family and colleagues, the general first reaction was usually related to the annual music festival. My stock response to this was ‘no’, and, if the mood was right, this was usually followed up by the fact that the Glastonbury Festival does not actually take place in the town of the same name.

Worthy Farm, the location of the festival, is situated just to the south of Pilton, six miles from Glastonbury. It was only called Glastonbury Festival because that was the nearest town people had heard of.

If you get the chance to make a quick pitstop from your journey to the south west, Pilton is definitely worth a visit. A genuine gem of a village, hidden in plain sight, it is also a good start and end point for a wander across the Levels or over the hilltops to Shepton Mallet.

There are many hurdles to be overcome.

But sometimes the scariest of challenges can bring the brightest of surprises.

Enjoy the moment.

As history moves on, it seems there were two main routes for villages to take. As we have seen, the first is to thrive, then to settle quietly into the background and become a quintessential English village, as with Haselbury Plucknett and Milverton (see previous posts).

The second option is not as positive, and this has been the route taken by the next village on our Somerset journey, Othery.

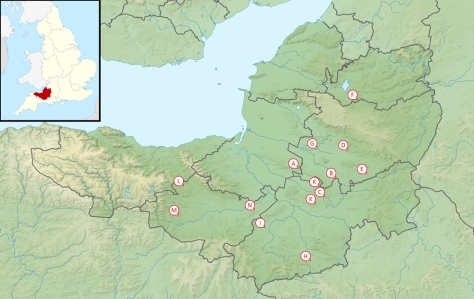

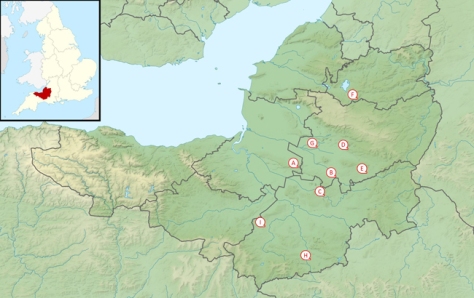

Sitting on the crossroads of the main roads between Bridgewater and Langport, Glastonbury/Street and Taunton, Othery once thrived as a stopping off point on the long journeys across sometimes threatening terrain.

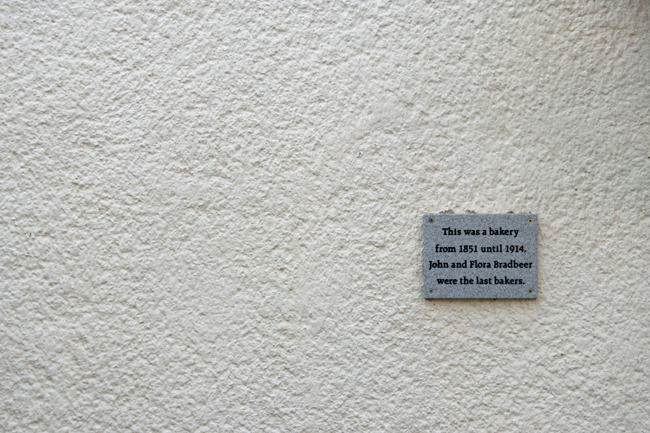

The Other Island sits 82ft (20m) above the surrounding moorland of the River Parrett, and so proved a good resting point for horses, carriages and passengers alike. For a population of around 500 people, this was once a bustling place, boasting three pubs, a post office, village store and bakery.

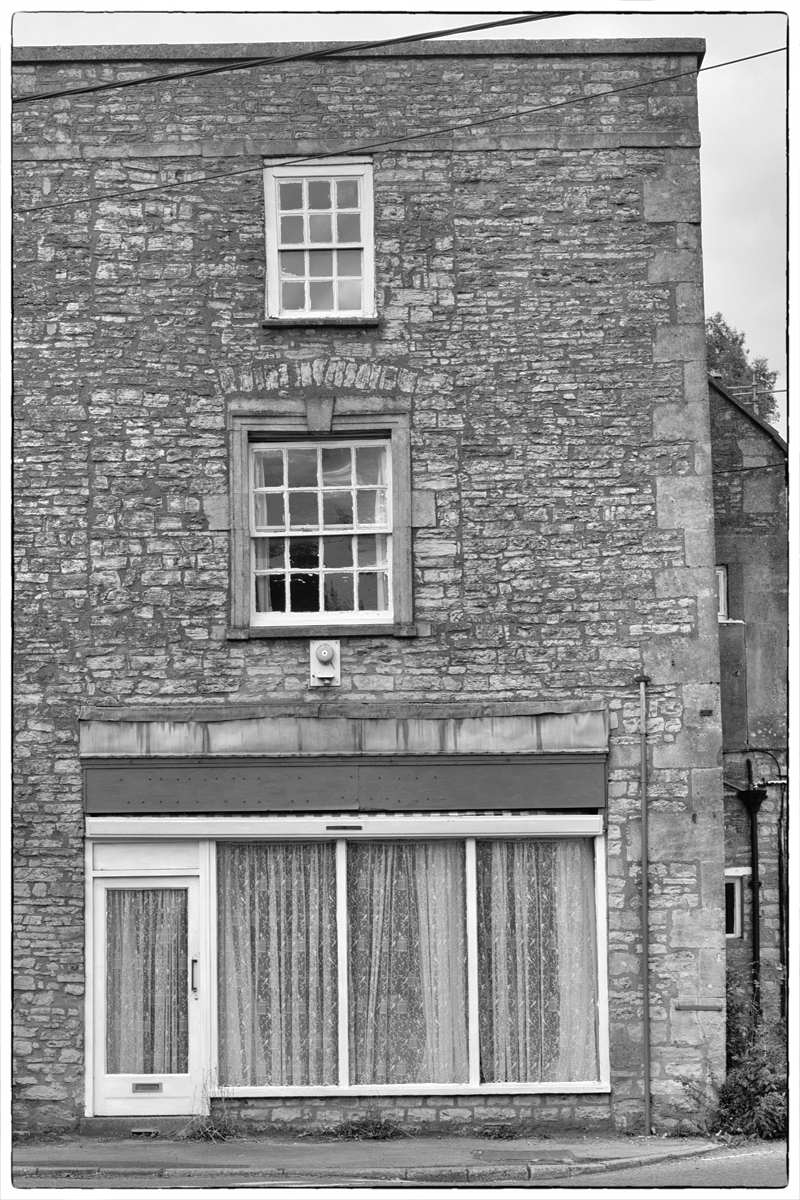

Sadly, the village has not thrived, and is nowadays more of a cut through, one of those places you see the road sign for, before slowing to 30mph and impatiently waiting for the national speed limit sign to come into view.

The buildings on the main road seem a little tired, once white frontages sullied by the dirt and grime of passing juggernauts. The signs outside the one remaining public house – the London Inn – almost beg you to stop, whether for a Sunday carvery or to watch weekend football matches on the huge TV screens.

(I admit the scaffolding does little to show the pub in its best light.)

But the fact of the matter is that, where once it would have had regular bookings, you can’t help feeling that this is very much a locals’ pub, whose inhabitants have set places at the bar and engraved tankards.

One glimmer of hope is that the the bakery seems to attract a lot of support. Again, it was closed when I stopped off here late one afternoon, but whenever I have driven through Othery before, there has tended to be a queue of people outside, and this gives a hint at a sense of community that the commuter doesn’t get to see.

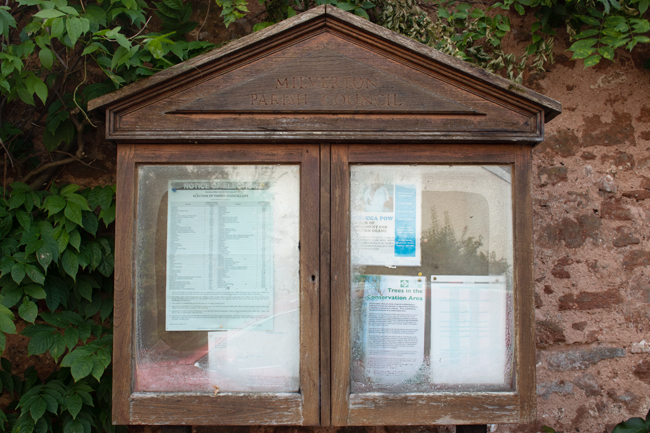

The community sense continues with the school sign too; a typical redbrick Victorian building enticing children in. Another sign of things changing is that, where this was once Othery Village School, it has now merged with neighbouring Middlezoy; families move out of the smaller villages, school numbers drop, changes take place to help support struggling services.

Move away from the main road, though, and you can see tantalising hints of what Othery once was, and probably still would be, had its position on the crossroads not been the main function of its existence.

North Lane is a much quieter affair than the main road. In between the mid-20th Century houses sit more stately structures, hidden behind high walls to shelter them from passing traffic.

St Michael’s Church stands proud above the village, helping direct the wayward and lost to a better life. You get the feeling, however, that locals stay behind their high walls more than they used to, something sadly echoed across rural Britain more than one might care to admit.

I am painting a pretty bleak picture, I know, but, while not deliberately doing the village down, this is the sense you get when exploring a place like Othery.

Where villages like North Curry once had glory, they were fortunate in their locale. Those villages that lie too short a distance from neighbouring towns have struggled in recent years, and Othery is not an exception.

Using the same stretch of road between Street and Taunton as an example, places like Walton, Greinton, Greylake, East Lyng, West Lyng and Durston have also struggled over the years.

Villages with a distinct pull, a unique selling point, like Burrowbridge on the same stretch of road, do survive, but for others it has been a struggle.

Additional housing projects have tried to rejuvenate them, but without the infrastructure to support them, the villages still die or get swallowed up by those neighbouring towns.

The unusual Somerset names continue as we head to the village of North Curry. Nothing to do with spicy food, the name is thought to derive from the Saxon or Celtic word for ‘stream’. There are a number of similarly named villages along this ridge to the east of Taunton – Curry Rivel, Curry Mallet and East Curry – but it is the North Curry that I found myself visiting.

Like Milverton, North Curry is a place that seems to have pretentions above its station. With a population of more than 1600 people, it is almost a town, but most of its wealth derives from its historic location – a dry ridge above water-logged marshes proved an ideal location for settlement from Roman times onwards.

The wealth is reflected in the number of large houses, particularly around the central green – Queen Square – and North Curry appears gentrified by Georgians and Victorians alike.

This sense of self importance is continued towards the north of the village, where the church – St Peter and St Paul’s – appears far larger than a place of North Curry’s size should accommodate. This is particularly the case, given that it is built on a ridge overlooking Haymoor and the River Tone – this is a building that was meant to be seen from afar and admired.

The central square is where the hub of life was focused. Sadly, the village’s post office/store and pub are all that remain of the old hustle and bustle. North Curry’s former wealth still remains on show, however, with a large memorial to Queen Victoria, an ornate War Memorial and a walled village garden being the focal points for today’s visitors.

While the wealth brought by through travellers may have long since departed, this is by no means a washed-up place. North Curry may be slightly off the beaten track, but it is still worth a wander around and there is plenty of opportunity to admire views and contemplate the wonder of the architecture.

Five miles to the west of Taunton lies the pretty village of Milverton. With a population of nearly 1500 people, it feels like more of a town, and the size and architecture of the houses hint at this being a bustling and rich place.

As with much of Somerset, the key trade was cloth, and a silk throwing factory was set up in the village at the beginning of the 19th century, eventually employing more than 300 people.

One of Milverton’s notable residents was Thomas Young (1773–1829). He is a man who had fingers in many pies, counting a scientific understanding of vision, light, solid mechanics, energy, physiology amongst his specialisms. He is probable more notable for his interest in Egyptology, and helped translate the Rosetta Stone.

The parish church is the Church of St Michael and All Angels, set in a quite location, and raised above the surrounding houses. It is a peaceful and tranquil location, perfect for reflection and contemplation.

A number of Commonwealth War Graves lie in the graveyard, which I’ll expand on in coming posts.

For a town of its size, Milverton has the amenities you would expect; there is another church – a Wesleyan Chapel built in 1850 – a school and a lone remaining public house, The Globe. Shops are minimal, as is transport – the village’s station was another of those that feel during the Beeching cuts of the 1960s.

One surprise, however, is the village’s High Street. Doing away with what we nowadays expect, there are no shops or conveniences on it; it is literally a high street, leading up a hill away from the church.

One thing I have found, as I reach the halfway point of my alphabetical journey around Somerset is that, while generally the same, all of the places I have visited have their distinct personalities.

Milverton has just that. It is a large village, the result of its previous industrial heritage, but has slipped back to become a sleepy locale, and is all the better for it.

In the depths of western Somerset, along country roads your SatNav smirks at taking you down, lies the pretty village of Lydeard St Lawrence.

The origins of the name is shrouded in a bit of mystery, but Lydeard may translate as “grey ridge”, while St Lawrence is the saint to whom the local church is dedicated. (It is likely that St Lawrence was added to the villae name, to distinguish it from the village of Bishop’s Lydeard, just four miles down the road.)

The village has a population of 500 people, and it is very easy to find yourself in open countryside within minutes of walking from the village centre.

The Church of St Lawrence is at the top end of the village and, as with may similar religious locations, is a calm and peaceful place to stop and rest.

A plaque on the gate into the churchyard pays tribute to Lance Corporal Alan Kennington, who was serving in Northern Ireland in 1973 when he was shot and killed while on foot patrol on the Crumlin Road, Belfast. He was just 20 years old.

The church also forms the last resting place for a number of other local men who passed away in the Great War – I’ll expand on these in later posts.

Lydeard St Lawrence, is certainly a peaceful village – on its own in the depths of the Somerset countryside and sheltered by the hills it is named after, it is somewhere to get away from it all. There are no immediate amenities – the post office has been closed long enough for the building to be converted into a house – but a village hall and school are there to support the community in all things secular.

I couldn’t let the lack f a J village pass, so I have included a second K in the list.

Just to the south of Kingweston, in between Somerton and Yeovil, sits the quiet village of Kingsdon.

With a population of just over 300 people, it is a tight-knit community, somewhere where, you readily find yourself walking along quiet roads, getting welcoming nods and hellos from local resident and dog-walkers.

The village gets is name from nearby Kingsdon Hill, which in turn reflects its regal connection to Somerton, a royal estate since the Norman Conquest.

All Saints Church, to the north of the village, is a peaceful location and dates back to the 1400s. The churchyard includes two Commonwealth War Graves, which I’ll explore in later blogs.

The community feel runs throughout Kingsdon, with a local pub, a phonebox book swap facility and a village school-cum-shop.

The views south are stunning too, heightening the real sense of countryside living. And, with plenty of footpaths locally, Kingsdon works well as a start point, finish, or stopping off point for an afternoon stroll.

Okay, so a slight hiccup in the A-Z proceedings in that there is no village (or town, or city) in Somerset that begins with the letter J. So, I will skip over that, and look at K instead.

And Kingweston is the stereotype for the evolution of a village.

It’s the end of the 11th Century. You’ve supported the winning side and so, as a reward, you are given the manor of Chinwardestune. It’s good farming land, and you have a nice house there. Over time – and changes of ownership – the manor has grown strong: you have a large house, alongside which you have built a church, there are farm buildings and cottages for your workers.

And that’s it. This village, with a population of less than 150, is little more than a farm, the attached manor house and its religious building and workers cottages.

The cottages are very picturesque; higgledy-piggledy on the lane up to the manor house and farm.

Walk up the main road and you encounter the Manor House. The barrier between those that had and those that had not. A high wall rings its lands, through the trees you get a glimpse of the grandeur within, but a glimpse is all you’re going to get.

The current Kingweston House was built in the 1800s by the long-term residents, the Dickinson family. In 1946 it was bought by Millfield School and has been used by them ever since.

The Church of All Saints is of a similar age to the manor house. Set at the upper end of the village, it is an ideal space for contemplation, as it overlooks the countryside towards Glastonbury Tor.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission suggests that Major Francis Arthur Dickinson is buried in the churchyard and, while I was unable to find his headstone, he is commemorated on the Roll of Honour in the church itself.

The plaque mentions other members of the Dickinson family who died during the Great War:

Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Carey Dickinson, of the Somerset Light Infantry and King’s African Rifles, died in Dar-es-Salaam in 1918.

Lieutenant George Barnsfather Dickinson of the East Lancashire Regiment fell at Ypres in May 1915.

The village has, understandably, a community feel to it. Even though the farm workers have move on and been replaced by wealthier country folk, Kingweston has a heart and a draw to it.

Tucked away deep in the countryside between Ilminster and Taunton is the picture perfect village of Isle Abbotts. Taking its name from the River Isle – which flows nearby – and Muchelney Abbey – whose lands it once sat on – Isle Abbotts is a tine village of little over 200 people.

And tucked away it is! I know I’m still fairly new to the county, but the road from Ilminster is as countrified as you get. High hedges on both sides, a strip of grass down the middle of the tarmac, battling tractors, a dog, some chickens and a Tesco lorry, it took a while to get there, but the journey was worth it.

There is a very chocolate box feel to Isle Abbotts; thatched cottages, a green, well tended gardens and cute village hall, the place is the epitome of the English country village.

There are two churches – The Blessed Virgin Mary and a baptist chapel (now a house, but the graveyard remains) – and the former is the heart of the village, as it should be. The majority of the graves are old and ornate, reminding you that the church was funded by – and therefore the domain of – the local landowners.

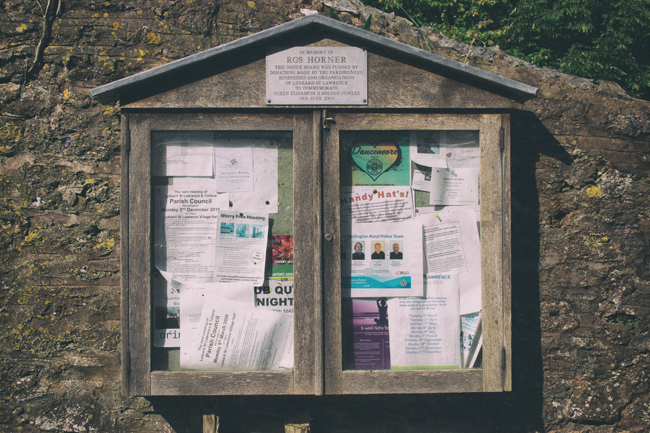

All the elements of a small community are there – a stone-built bus stop and information board, a hall with a stand for second-hand books, a sun-bleached telephone box, a tree planted to commemorate the Silver Jubilee in 1977.

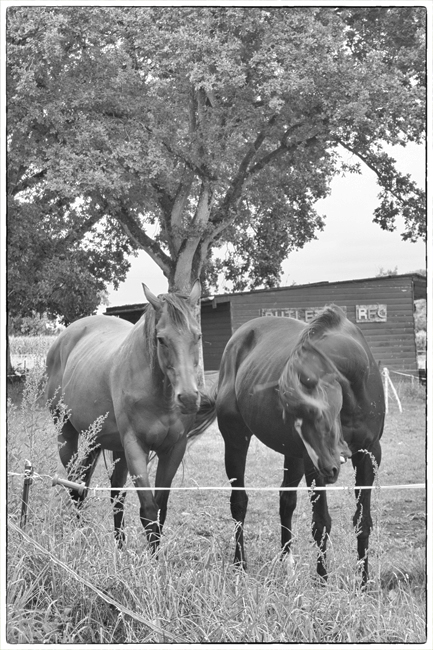

But the bigger reminder of the connection between Isle Abbotts and the countryside around it is the farmland.

It is very easy to get right back into the countryside from the village centre, passing through farmland, you come to a bridge across the River Isle, from where a track passes to the neighbouring village of Isle Brewers.

(Smaller in population than Abbotts, Isle Brewers takes its name not from beer-making, but from the the family of William Briwere, lord of the manor in the 1200s.)

At this end of the village, the Manor Farm dominates the landscape, and you readily remember that this is what would have provided labour for the majority of the population in days gone by.

Quiet, isolated, but calm and peaceful, this is definitely a place that reminds you to get out in the sticks, get away from town and city life and enjoy the open air.

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....