#171

It is good to be busy, but to work at our best, you need to take a pause.

Stop, breathe, recharge.

It’s good to keep busy.

It’s just as good to take a step back.

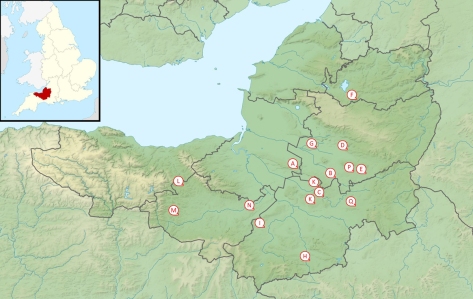

Just to the north west of Yeovil lies the quiet village of Tintinhull. The derivation of its name is steeped in mystery – ‘tin’ meant ‘fort’ in old English and ‘examine’ in Saxon, while ‘hull’ is an old term for ‘hill’. The village sits in the lea of Ham Hill, so a combination of elements seems likely.

Tintinhull has a population of just over a thousand people, and the manor dates back to pre-Norman times. The local Saxon tribes used to avoid siting their villages on the old Roman roads, so the village sits just away from the Fosse Way (now the A303).

Most of the houses in the village are made from Ham stone – quarried from the local hill – and this gives a quaint, consistent feel to the place. A lot of the original cottages are thatched and, barring the telegraph poles and cars, Tintinhull has the typical chocolate-box feel you would expect of a West Country village.

There is not an immediate heart to the Tintinhull – the village green is surrounded by cottages – but there are plenty of gathering places, both contemporary and historic.

Opposite the new Village Hall, the old Lamb Inn has been tastefully converted to cottages and in the same stretch of road the old Working Men’s Club still bears the Toby Bitter advertising sign.

The remaining village pub – the Crown & Victoria – is set on the way to the manor house, and was obviously the stopping off point for farm workers ending their shift and returning home.

The manor house itself is now owned and run by the National Trust, and it is the connected Tintinhull Gardens that now draw people to this part of Somerset. (Sadly, due to the time of year and the restrictions imposed by the coronavirus pandemic, the gardens were not open at the time of visiting.)

Most of the villages I have visited on this alphabetical journey include the main elements of the manor house, a school, a gathering place and the church, and Tintinhull is no exception.

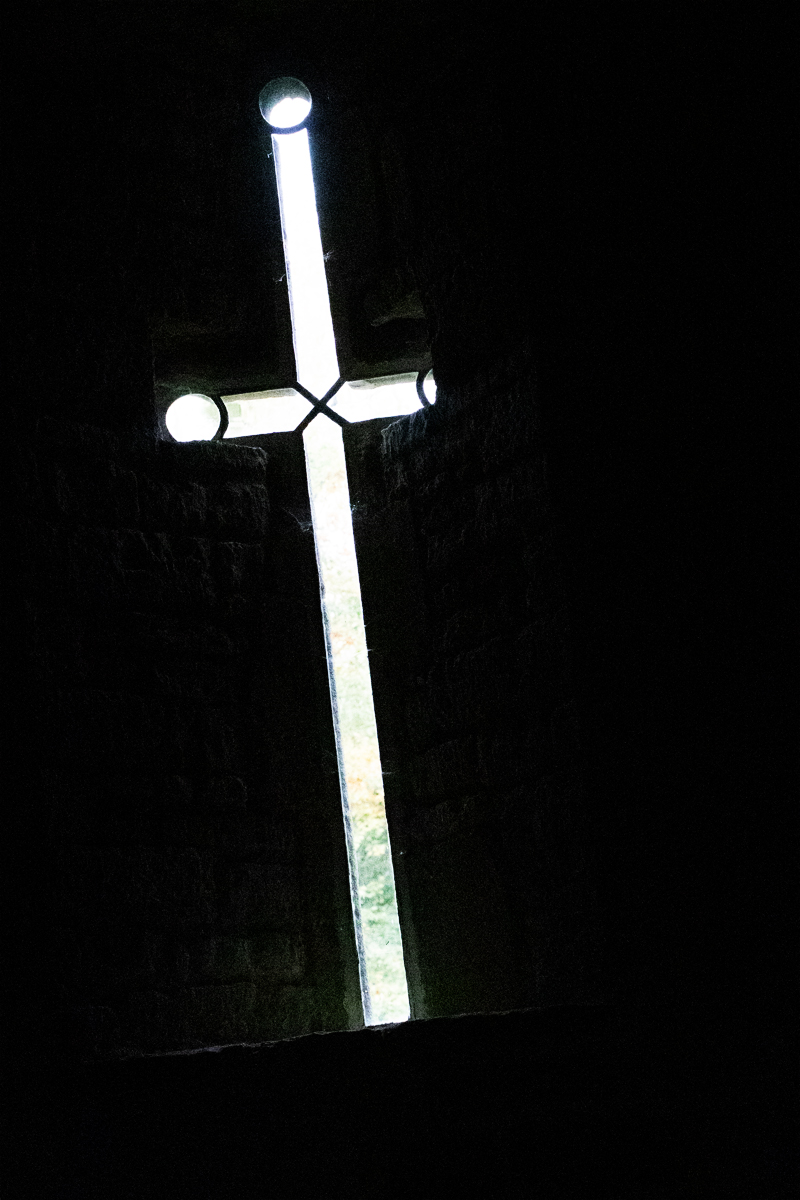

St Margaret’s Church sits away from the manor house – unusual, as they are normally intrinsically linked. As with most village churchyards, it is a peaceful place, somewhere to reflect and gather one’s thoughts.

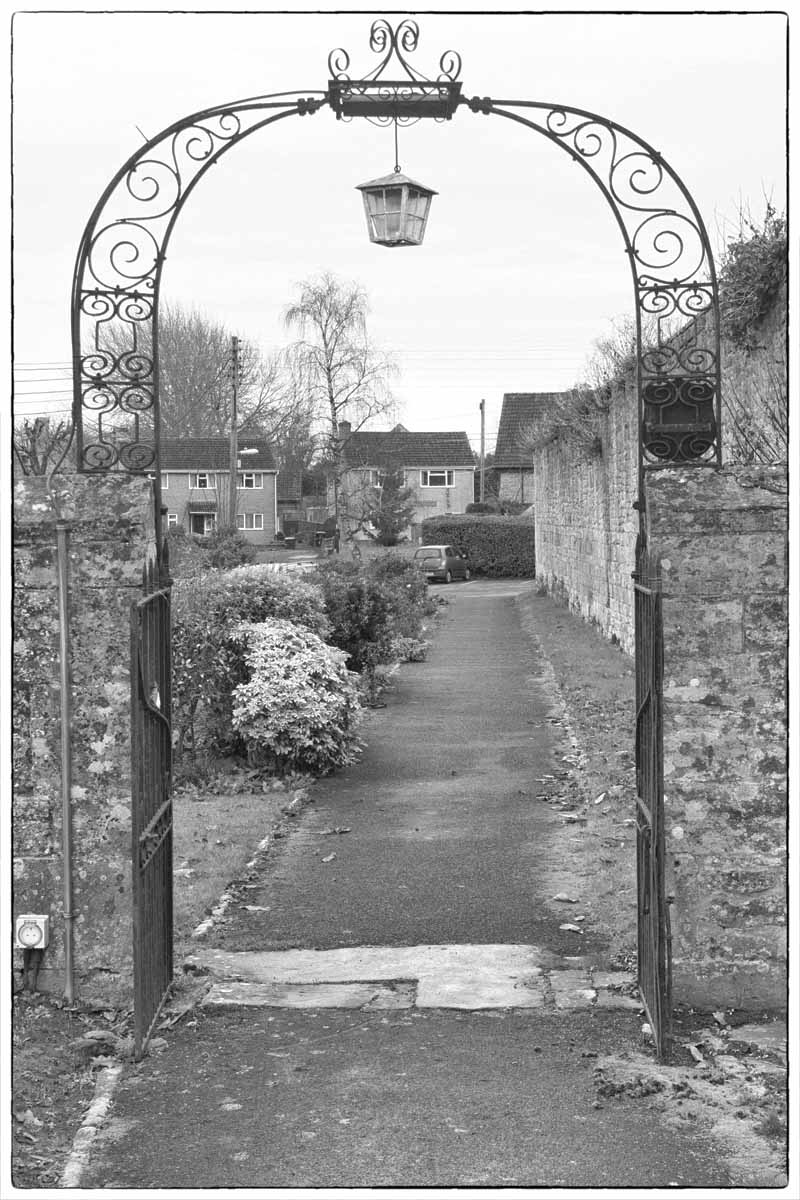

Approached by way of a long path, you feel a sense of great reverence as you walk towards St Margaret’s; this sensation is added to by the imposing wall on the left of the path, hiding a dramatic house behind it.

Once in the churchyard itself, the extent of the building behind the wall is revealed; this is Tintinhull Court, in its medieval glory.

Originally the parsonage, it was first built by the abbot of nearby Montacute Priory; remodelled three times since its original construction, it has been designated a Grade I building.

The history of Tintinhull Court begins to make more sense of the village layout; this was the original manor house and its owners built the church next door, with window overlooking the the graveyard and the parishioners walking towards their weekly sermon.

The resident Napper family built Tintinhull House – on the other side of the village – as a dower house in the seventeenth century; close enough that the Court’s widow was in walking distance, but far enough away for her not to disturb the ongoing matters of her heirs.

The graveyard also commemorates three residents who fell on home oil during the First World War.

To find out more about the lives of Private William Newman, Stoker Henry Lucas and Boy Albert Matthews, follow the links, or head over to the CKPonderingsCWG website.

Tintinhull has a long history, and economically it has survived well; primarily an agricultural community, the village has also been a focus for glove-making, dating back as far as the thirteenth century. By the late nineteenth century, much of the village’s employment came from the industry, and it continues today, although on a much reduced level.

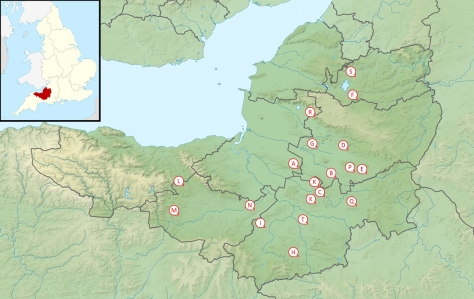

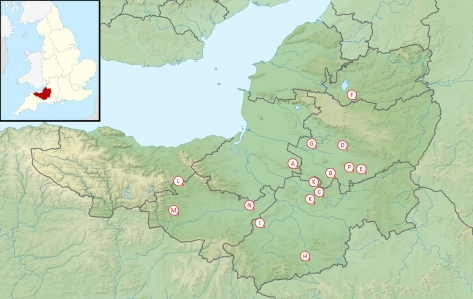

In the north of the county*, just eight miles from the centre of Bristol lies the quiet village of Stanton Drew. Nestled in the rolling hills of this part of the county, it is easily overlooked. (Avoid using your SatNav – you will end up encountering all sorts of twisty turny country roads!!)

Old enough as a village to have featured in the Domesday Book, it was listed as Stantone, from the Old English and Celtic words meaning “the stone enclosure with an oak tree”.

Drew came from the name of one of the former owners of the area, and was added to distinguish the place from neighbouring Stanton Wick and Stanton Prior.

Approaching from the north, the first hint of Stanton Drew comes from the sight of the unusual Round House. Originally a tollhouse, this quirky thatched building sets the tone for the other buildings in the village.

Over the narrow bridge, and you arrive at the village itself.

You very readily identify that this was once a place of great wealth. There are a number of large properties, and it is difficult to identify if there was ever just one manor house.

Stanton Drew gained its wealth from coal, and, at, as late as the 1950s, there were as many as three mines within the parish boundaries.

In fact, there is little evidence of any smaller housing; yes the land around the village is also good for agriculture, but there aren’t many traditional farming cottages to be found.

The main religious site is the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which dates to the 13th and 14th centuries.

As befits a village of this stature, there is a school and village pub, but as you wander round Stanton Drew, you can’t help but get the feeling there there is something more about this place, something that you cannot quite put your finger on.

And oddly, it’s the garden of the village pub – The Druid’s Arms – that gives you the first hint.

For while Stanton Drew was first listed in the Domesday Book, its history significantly predates this writing from 1086.

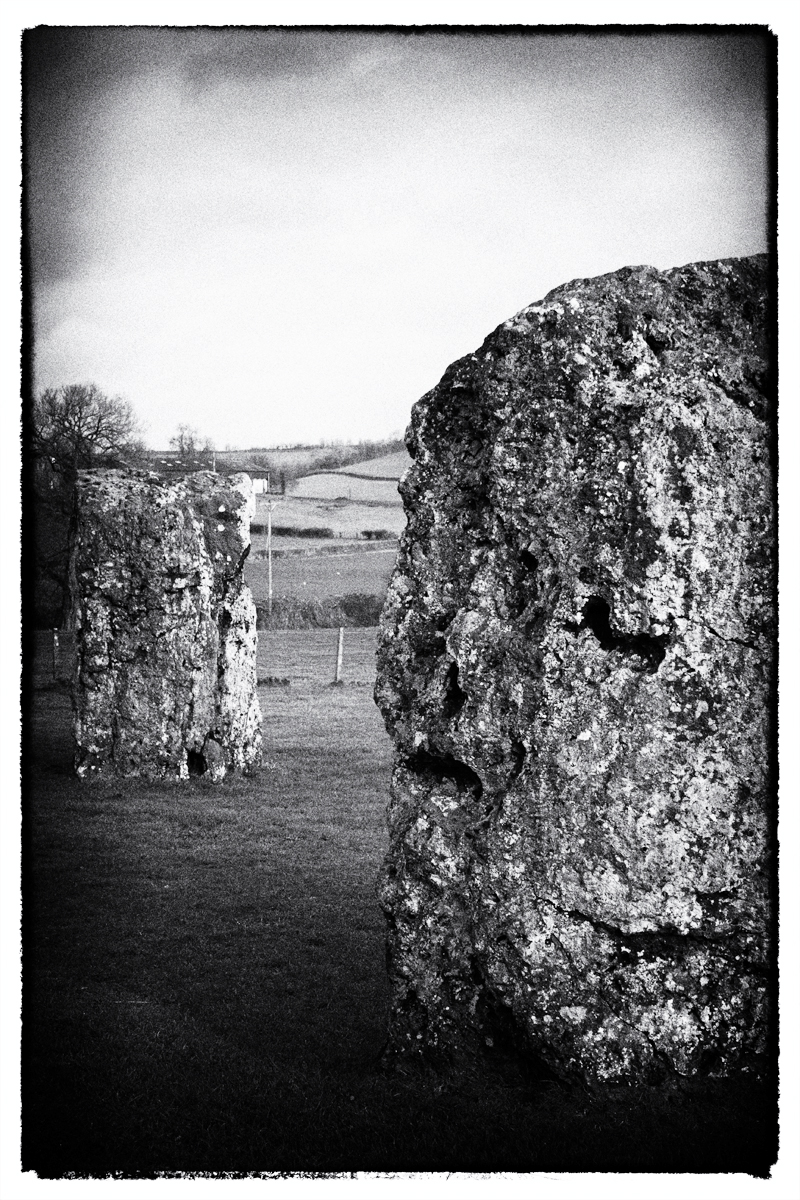

Three stones form a prehistoric enclosure, within site of the village church. They hint at the ceremonial activities which took place here around 4,500 years ago.

They are also said to be the relics of a parson, bride and bridegroom, turned to stone by the Devil because their wedding guests danced on a Sunday.

Behind the church as the most impressive element of Stanton Drew.

Three stone circles, up to 371 ft (113m) in diameter lie to the east and north of the village. Contemporary in date to the Neolithic site at Stonehenge, the Great Stanton Drew circle is, in fact, larger than its more well-known Wiltshire counterpart.

Only the stone circle at Avebury is bigger in size, meaning that the Stone Age circles of Stanton Drew are, in fact, the second largest Neolithic site in the United Kingdom.

Significantly less visited than either Avebury or Stonehenge, Stanton Drew is one of the country’s best kept prehistoric secrets.

Undoubtedly one of the places to visit in the county, there is plenty to admire in Stanton Drew, and, for history buffs and walkers alike, there is more than enough to see and do.

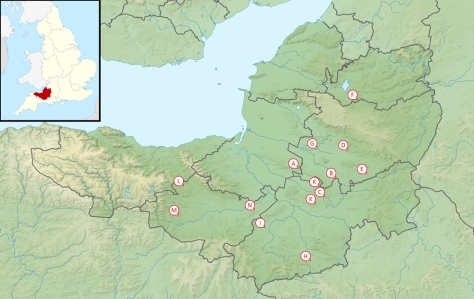

* While Stanton Drew lies in the Bath and North East Somerset Unitary Authority, is is still part of the ceremonial county of Somerset, and so is happily included as part of this A-Z wandering.

At the foothills of the Mendips, on the main road between Wells and Weston-super-Mare, lies the quiet, unassuming village of Rodney Stoke. Owned by a number of families over the years, Stoches (old English for ‘settlement’) has been known as Stoke Whiting, Stoke Giffard and Stoke Rodney over the years, before the name settled on Rodney Stoke.

With a population of close to 1,500 people, you would expect the village to be a bustling affair, but settled as it is – along three lanes leading downhill from the A371 – it has an altogether quieter feel about it.

The lanes are lined with cottages built for former farm workers. Some former outbuildings have been converted into newer residences while other parts of the village are much newer properties, albeit still in keeping with the history of the village.

At the bottom of Stoke Street lies a farm, while the former manor house stands proud above the surrounding fields.

The parish church – St Leonard’s – is, unsurprisingly, place next to the manor house and, while hidden from most of the village, it can be clearly seen on the skyline from the south, standing tall and proud against the dramatic escarpment of the Mendips.

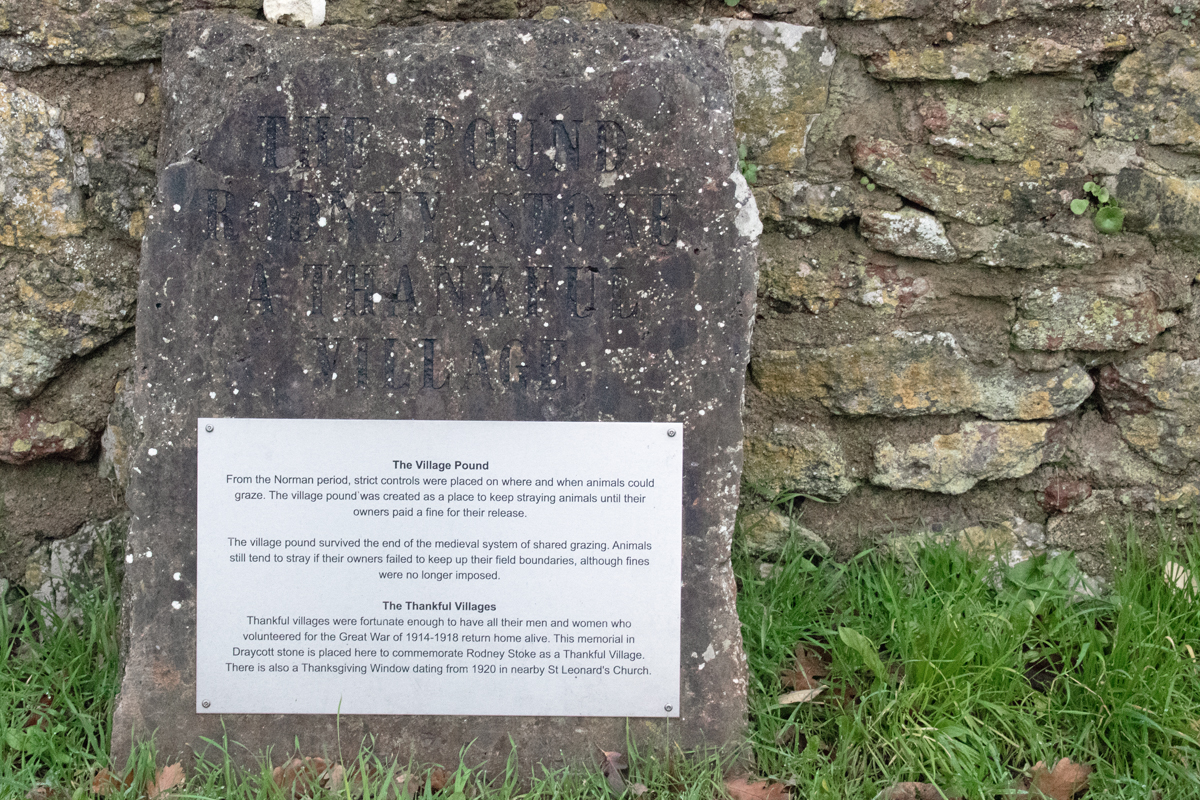

Normally, when I visit the local villages, I spent time in the churchyard looking for Commonwealth War Graves. However, Rodney Stoke stands out as one of the county’s Thankful Villages.

Fifty-three parishes in England and Wales are commemorated as having sent servicemen to war between 1914 and 1918, all of whom returned at the end of the conflict. These Thankful Villages stand out, particularly given that there are tens of thousands of towns and villages across the country.

Somerset has the highest number of Thankful Villages by county, with Rodney Stoke counting as one of nine. This is celebrated by a window in the church, giving thanks that “All glory be to God, whom in his tender mercy has brought again to their homes, the men and women of Rodney Stoke who took part in the Great War 1914-1919”.

(As an aside, Rodney Stoke sadly doesn’t fit into the category of being Doubly Thankful, having seen all of their service men and women return from both world wars. Four local residents – David Cooper, John Glover-Price, Denis Thayer and James Williams – perished in the 1939-1945 conflict.)

A second memorial to Rodney Stoke being thankful is situated in the Village Pound.

Since Norman times, strict controls were in place about where and when animals could graze on common land. The Pound – a walled area on the main road – was a place for straying animals to be kept until their owners paid the due fine.

As with other villages I have visited for this alphabetical journey, Rodney Stoke is definitely worth stopping by for. To the north of the village lie the Stoke and Stoke Woods Nature Reserves , and the village pub – the Rodney Stoke Inn – must also be worth a visit!

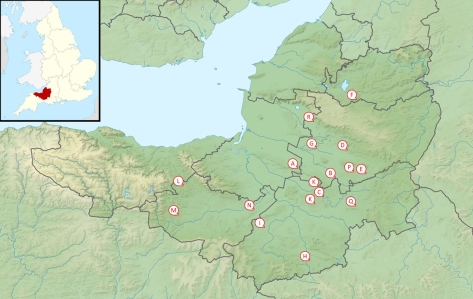

Seven miles to the north of Yeovil, lies the unusually-named village of Queen Camel. While it sits on the main A359 road, this thoroughfare dog-legs through the village, so it avoids the speeding traffic of which Othery is a victim.

The name derives from the old English word cam, meaning ‘bare rim of hills’, a word shared by the river that runs through the village. The manor of Camel was given to the crown in the late 13th century, and the name was changed to Camel Regis (“King’s Camel”). Edward I gave the area to his wife, Eleanor, and so the name Queen Camel was born.

One of the highlights of the village is Church Path, a cobbled road that leads from the centre of Queen Camel to St Barnabas’ Church.

The church itself dates from the 1300s, and, despite the main road, is surrounded by a quiet churchyard and allotments. Additional architectural elements – including an imposing porch on the south side – were added in the 19th century, as part of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebrations.

The churchyard includes a gravestone to Seaman Donald Burgess, who died in the Great War, aged just 17 years old.

Details of his life can be found on the CKPonderingsCWG site, which is dedicated to those who lost their lives as a result of that conflict.

The houses in the village are all local stone, and while some are from the early 2000s, they fit in almost seamlessly with the old structures around them.

The Mildmay Arms is the village pub; again, it is reminiscent of a coaching inn, and was likely used as such at some point in its history.

Queen Camel has an undoubted village feel; with a population of less than 1000 people, there is a definite sense of community here.

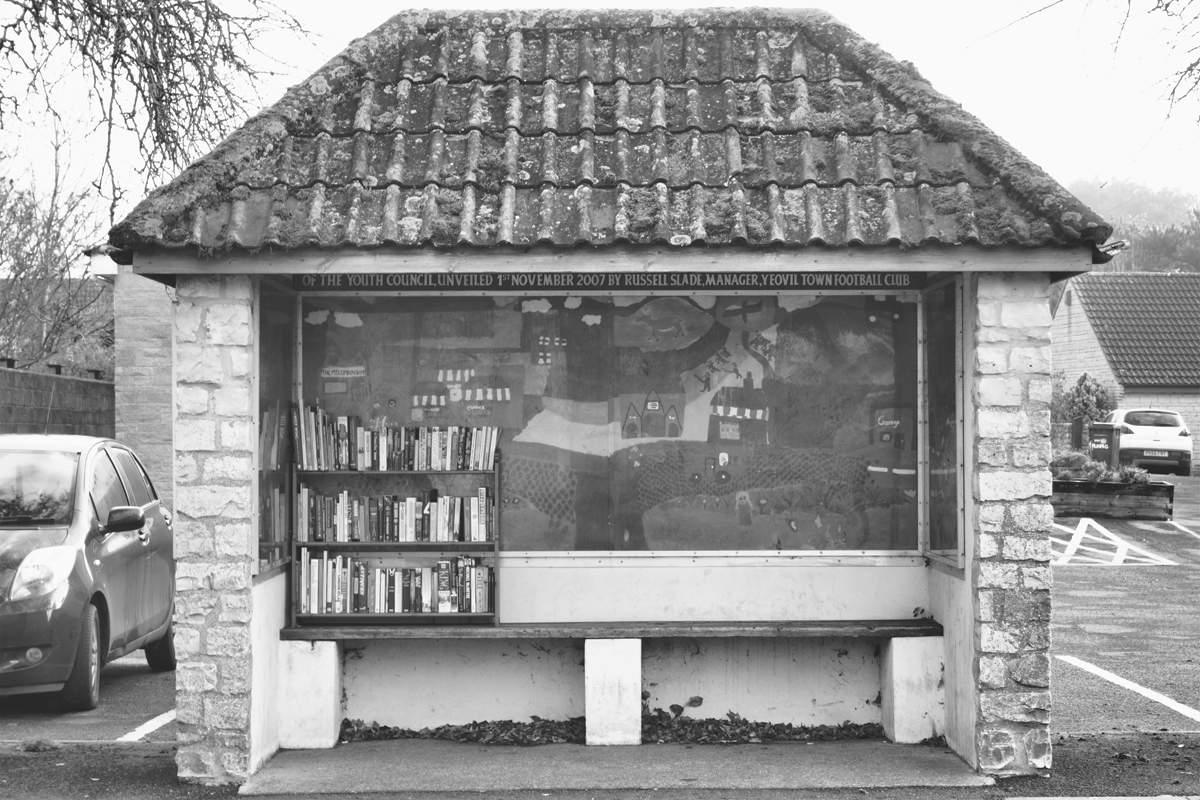

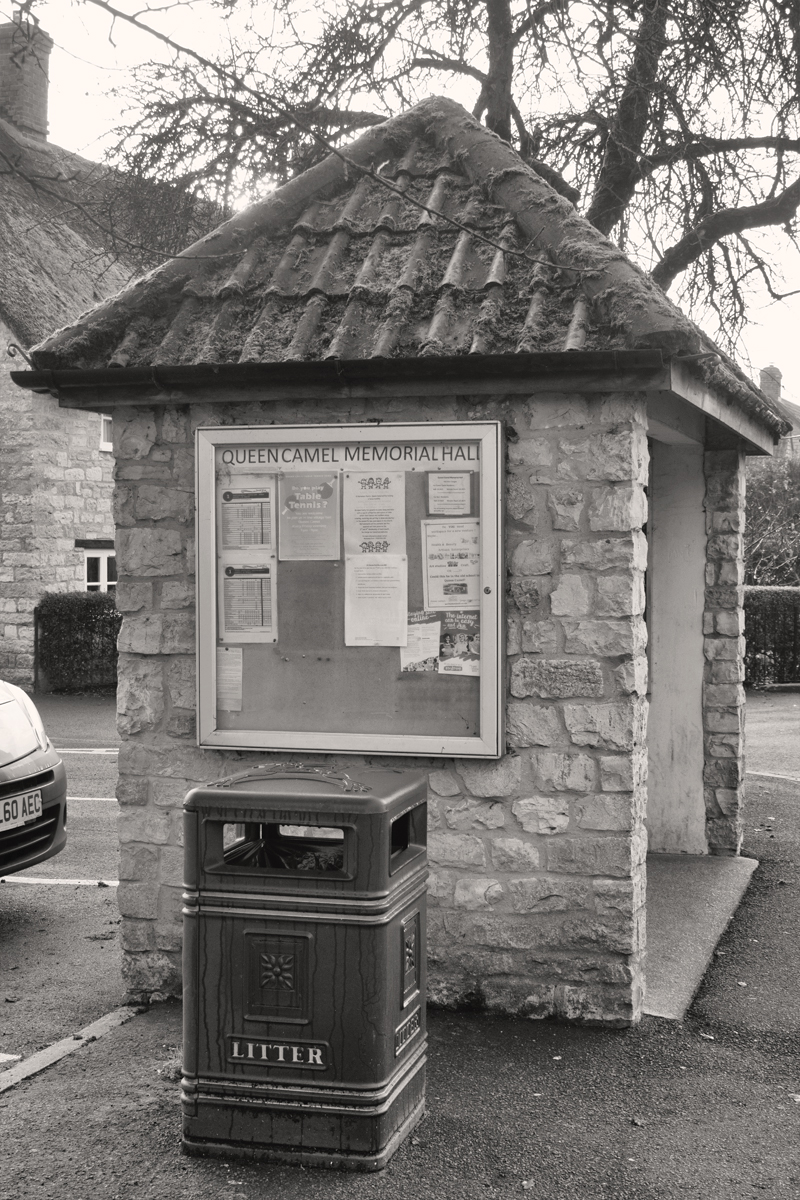

A former bus stop – standing outside the Memorial Hall – now houses a mural dedicated to the village’s history, as well as a book swap station.

There is a lane in Queen Camel that is dedicated to a Grace Martin; I have not been able to find out much about her. There is someone by that name – the daughter of John and Judith Martin – baptised in St Barnabas’ Church in July 1744. Beyond that she remains a mystery.

Despite its location, Queen Camel is a peaceful place to visit; a lovely addition to the Somerset A to Z.

Continue up the A361 for 16 miles from Othery and you reach the surprising village of Pilton. I have driven through the village countless times over the years, and there is so much more to it than what is visible from the main road.

Situated on the top of a hill to the east on Glastonbury, the village once overlooked an inland sea that stretched to the present day Bristol Channel. This lead to the village’s original name, Pooltown, because ships were able to navigate this far inland.

The houses in the village are old, from local stone, and really fit in with the country feel. Despite the main road, laden with juggernauts, being close by, the majority of the village is in a sheltered valley, and within a matter of metres away from the A361, it can barely be heard.

The local church is St John the Baptist, which is on the north side of the valley, has a commanding view across all Pilton. Once again, the Church’s dominance is in plain sight, and it can be seen on the skyline from most of the houses.

In the churchyard is a memorial, a grave to Sapper Percy Wright Rodgers, who fell in the First World War. More information on this young man’s life can be found on the CKPonderingsCWG blog, along with more stories of the fallen of the Great War.

To the south of the village, a tithe barn stands alone and proud. Once belonging to Glastonbury Abbey, the barn once stored local farmers’ produce, of which they gave the Abbey – the landowner – one tenth.

The barn is now a Grade 1 listed building.

In the barn’s grounds is a monument to the Land Armies of both world wars; a bench in a quiet corner of an already quiet corner of the village is perfect for contemplation.

When I first made my intention of moving to Somerset known to friend, family and colleagues, the general first reaction was usually related to the annual music festival. My stock response to this was ‘no’, and, if the mood was right, this was usually followed up by the fact that the Glastonbury Festival does not actually take place in the town of the same name.

Worthy Farm, the location of the festival, is situated just to the south of Pilton, six miles from Glastonbury. It was only called Glastonbury Festival because that was the nearest town people had heard of.

If you get the chance to make a quick pitstop from your journey to the south west, Pilton is definitely worth a visit. A genuine gem of a village, hidden in plain sight, it is also a good start and end point for a wander across the Levels or over the hilltops to Shepton Mallet.

As history moves on, it seems there were two main routes for villages to take. As we have seen, the first is to thrive, then to settle quietly into the background and become a quintessential English village, as with Haselbury Plucknett and Milverton (see previous posts).

The second option is not as positive, and this has been the route taken by the next village on our Somerset journey, Othery.

Sitting on the crossroads of the main roads between Bridgewater and Langport, Glastonbury/Street and Taunton, Othery once thrived as a stopping off point on the long journeys across sometimes threatening terrain.

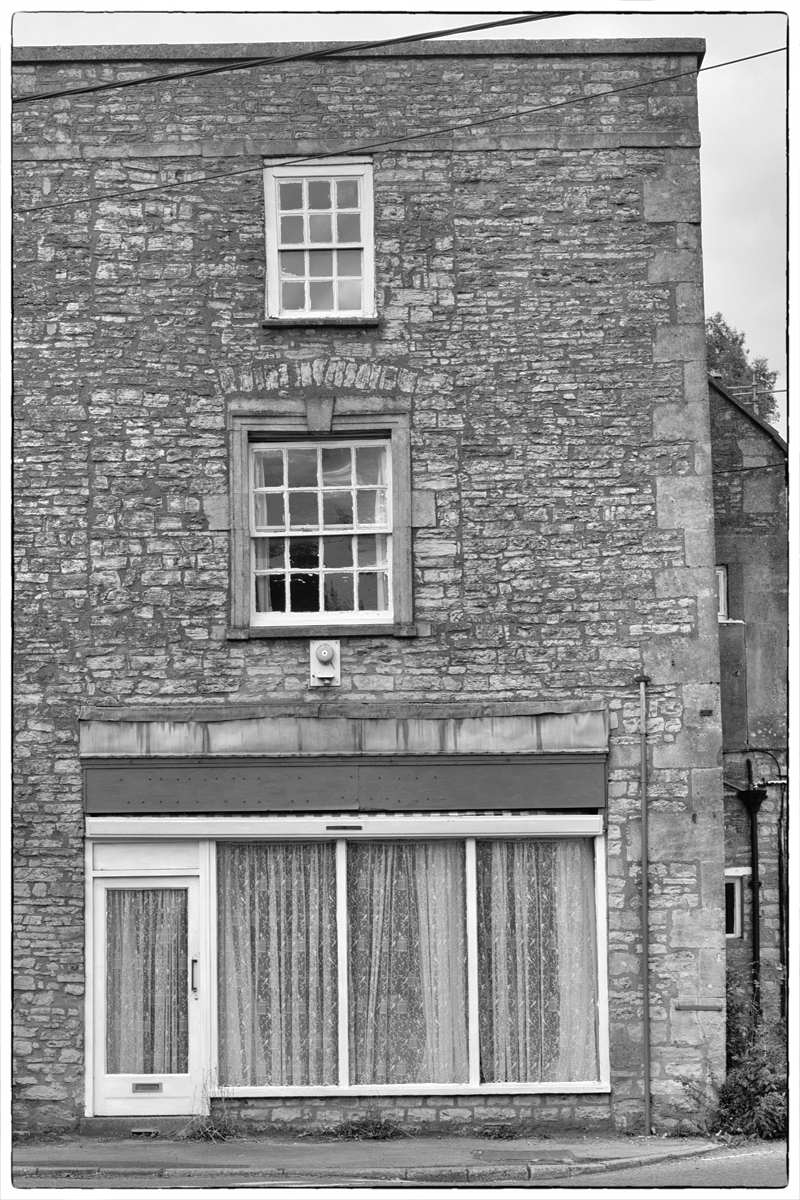

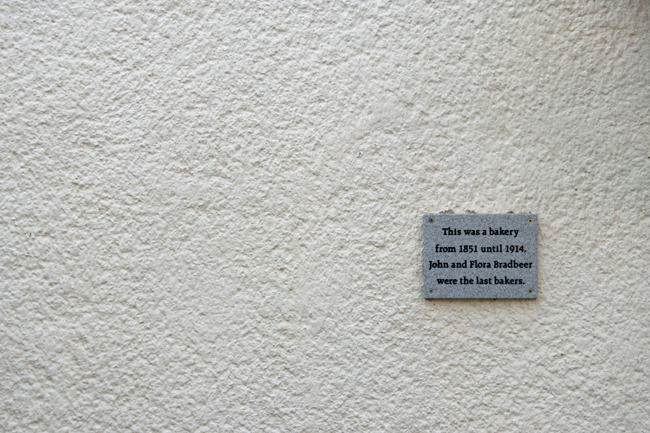

The Other Island sits 82ft (20m) above the surrounding moorland of the River Parrett, and so proved a good resting point for horses, carriages and passengers alike. For a population of around 500 people, this was once a bustling place, boasting three pubs, a post office, village store and bakery.

Sadly, the village has not thrived, and is nowadays more of a cut through, one of those places you see the road sign for, before slowing to 30mph and impatiently waiting for the national speed limit sign to come into view.

The buildings on the main road seem a little tired, once white frontages sullied by the dirt and grime of passing juggernauts. The signs outside the one remaining public house – the London Inn – almost beg you to stop, whether for a Sunday carvery or to watch weekend football matches on the huge TV screens.

(I admit the scaffolding does little to show the pub in its best light.)

But the fact of the matter is that, where once it would have had regular bookings, you can’t help feeling that this is very much a locals’ pub, whose inhabitants have set places at the bar and engraved tankards.

One glimmer of hope is that the the bakery seems to attract a lot of support. Again, it was closed when I stopped off here late one afternoon, but whenever I have driven through Othery before, there has tended to be a queue of people outside, and this gives a hint at a sense of community that the commuter doesn’t get to see.

The community sense continues with the school sign too; a typical redbrick Victorian building enticing children in. Another sign of things changing is that, where this was once Othery Village School, it has now merged with neighbouring Middlezoy; families move out of the smaller villages, school numbers drop, changes take place to help support struggling services.

Move away from the main road, though, and you can see tantalising hints of what Othery once was, and probably still would be, had its position on the crossroads not been the main function of its existence.

North Lane is a much quieter affair than the main road. In between the mid-20th Century houses sit more stately structures, hidden behind high walls to shelter them from passing traffic.

St Michael’s Church stands proud above the village, helping direct the wayward and lost to a better life. You get the feeling, however, that locals stay behind their high walls more than they used to, something sadly echoed across rural Britain more than one might care to admit.

I am painting a pretty bleak picture, I know, but, while not deliberately doing the village down, this is the sense you get when exploring a place like Othery.

Where villages like North Curry once had glory, they were fortunate in their locale. Those villages that lie too short a distance from neighbouring towns have struggled in recent years, and Othery is not an exception.

Using the same stretch of road between Street and Taunton as an example, places like Walton, Greinton, Greylake, East Lyng, West Lyng and Durston have also struggled over the years.

Villages with a distinct pull, a unique selling point, like Burrowbridge on the same stretch of road, do survive, but for others it has been a struggle.

Additional housing projects have tried to rejuvenate them, but without the infrastructure to support them, the villages still die or get swallowed up by those neighbouring towns.

The unusual Somerset names continue as we head to the village of North Curry. Nothing to do with spicy food, the name is thought to derive from the Saxon or Celtic word for ‘stream’. There are a number of similarly named villages along this ridge to the east of Taunton – Curry Rivel, Curry Mallet and East Curry – but it is the North Curry that I found myself visiting.

Like Milverton, North Curry is a place that seems to have pretentions above its station. With a population of more than 1600 people, it is almost a town, but most of its wealth derives from its historic location – a dry ridge above water-logged marshes proved an ideal location for settlement from Roman times onwards.

The wealth is reflected in the number of large houses, particularly around the central green – Queen Square – and North Curry appears gentrified by Georgians and Victorians alike.

This sense of self importance is continued towards the north of the village, where the church – St Peter and St Paul’s – appears far larger than a place of North Curry’s size should accommodate. This is particularly the case, given that it is built on a ridge overlooking Haymoor and the River Tone – this is a building that was meant to be seen from afar and admired.

The central square is where the hub of life was focused. Sadly, the village’s post office/store and pub are all that remain of the old hustle and bustle. North Curry’s former wealth still remains on show, however, with a large memorial to Queen Victoria, an ornate War Memorial and a walled village garden being the focal points for today’s visitors.

While the wealth brought by through travellers may have long since departed, this is by no means a washed-up place. North Curry may be slightly off the beaten track, but it is still worth a wander around and there is plenty of opportunity to admire views and contemplate the wonder of the architecture.

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....