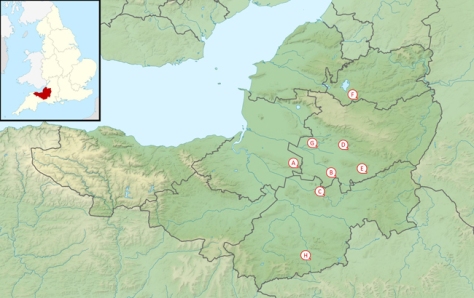

Okay, so a slight hiccup in the A-Z proceedings in that there is no village (or town, or city) in Somerset that begins with the letter J. So, I will skip over that, and look at K instead.

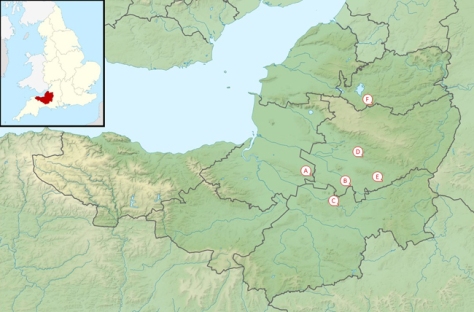

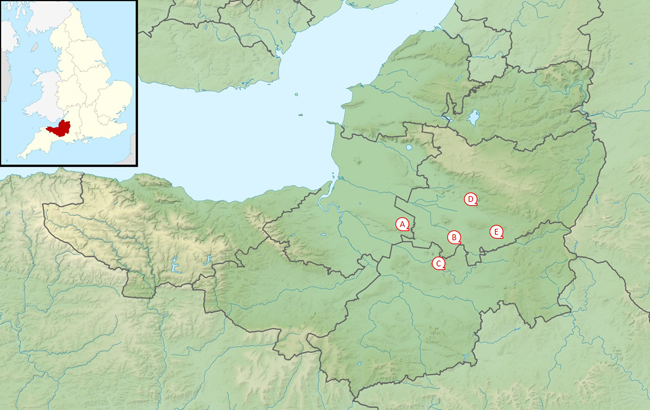

And Kingweston is the stereotype for the evolution of a village.

It’s the end of the 11th Century. You’ve supported the winning side and so, as a reward, you are given the manor of Chinwardestune. It’s good farming land, and you have a nice house there. Over time – and changes of ownership – the manor has grown strong: you have a large house, alongside which you have built a church, there are farm buildings and cottages for your workers.

And that’s it. This village, with a population of less than 150, is little more than a farm, the attached manor house and its religious building and workers cottages.

The cottages are very picturesque; higgledy-piggledy on the lane up to the manor house and farm.

Walk up the main road and you encounter the Manor House. The barrier between those that had and those that had not. A high wall rings its lands, through the trees you get a glimpse of the grandeur within, but a glimpse is all you’re going to get.

The current Kingweston House was built in the 1800s by the long-term residents, the Dickinson family. In 1946 it was bought by Millfield School and has been used by them ever since.

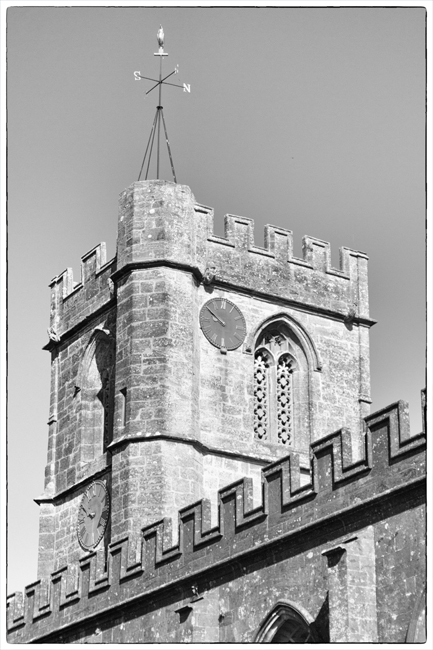

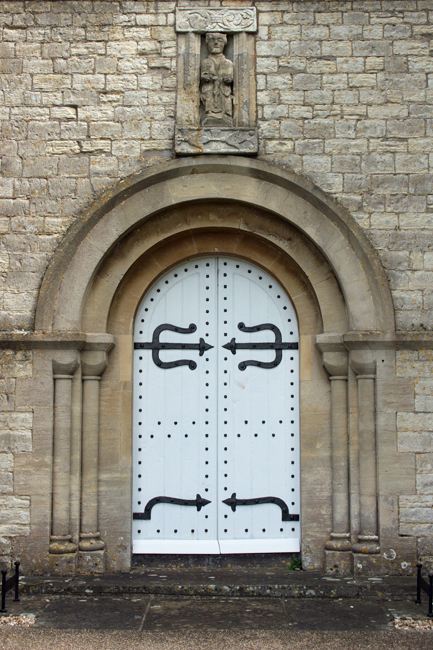

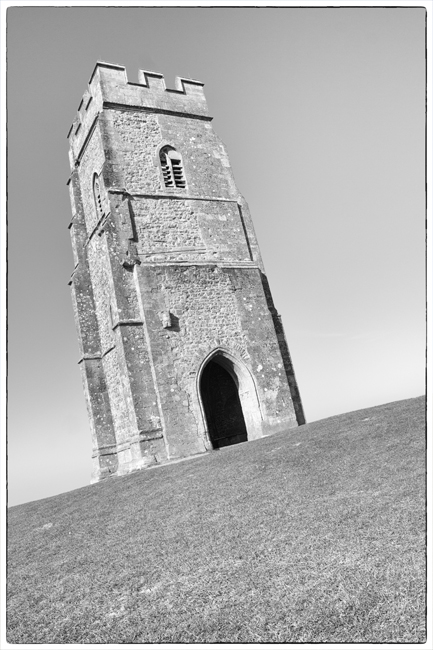

The Church of All Saints is of a similar age to the manor house. Set at the upper end of the village, it is an ideal space for contemplation, as it overlooks the countryside towards Glastonbury Tor.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission suggests that Major Francis Arthur Dickinson is buried in the churchyard and, while I was unable to find his headstone, he is commemorated on the Roll of Honour in the church itself.

The plaque mentions other members of the Dickinson family who died during the Great War:

Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Carey Dickinson, of the Somerset Light Infantry and King’s African Rifles, died in Dar-es-Salaam in 1918.

Lieutenant George Barnsfather Dickinson of the East Lancashire Regiment fell at Ypres in May 1915.

The village has, understandably, a community feel to it. Even though the farm workers have move on and been replaced by wealthier country folk, Kingweston has a heart and a draw to it.