The next in the A-Z is one that potentially challenges what I am looking to achieve in a list of Somerset villages as it examines what actually constitutes a village.

In England, at least, you have hamlets, villages, towns and cities.

- Hamlets have no central place of worship and no meeting point (for example a village hall).

- Villages have one central place of worship and a meeting point.

- Towns have more than one of each and will often have a charter to hold a weekly market; they will also have their own form of council.

- Cities are larger conurbations with multiple places of worship and meeting points.

So, why bring this up now?

Well, the issue with the next place I have visited is that technically it is not a village.

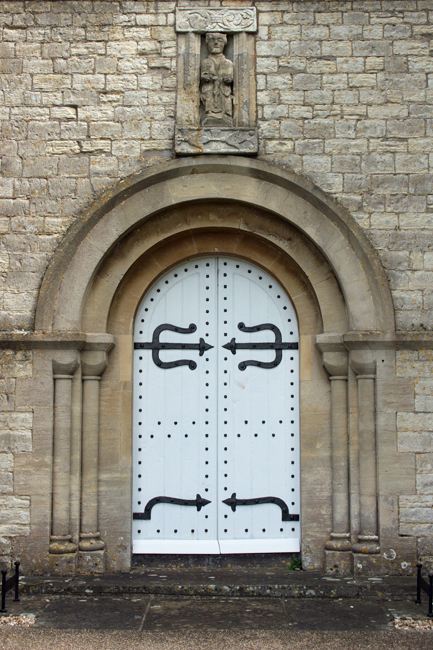

Godney has a handful of houses, a farm and a small church (Holy Trinity), but no meeting point.

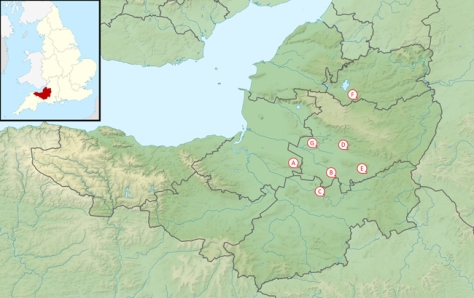

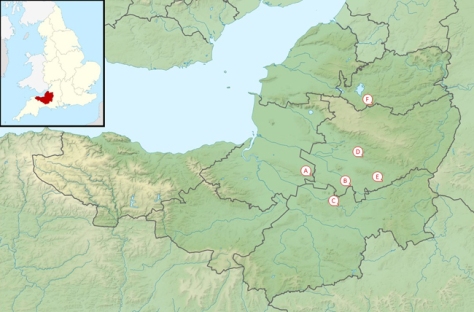

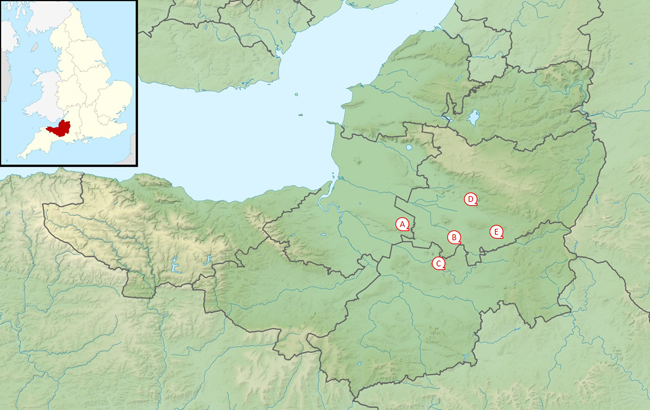

It lies just to the north of Glastonbury, on a small rise overlooking the River Sheppey.

Why am I including Godney in the A-Z, then? Well, on the other side of the river are two other hamlets – Upper Godney and Lower Godney – and between the three of them, they meet all of the requirements of a village.

So, then, I am looking at The Godneys, not just Godney itself. (Okay, it’s a bit of a stretch, but they’re nice places!)

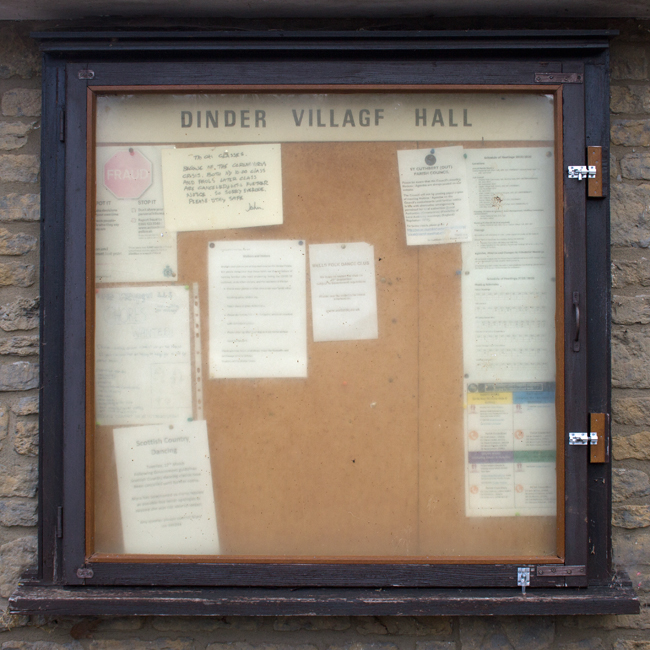

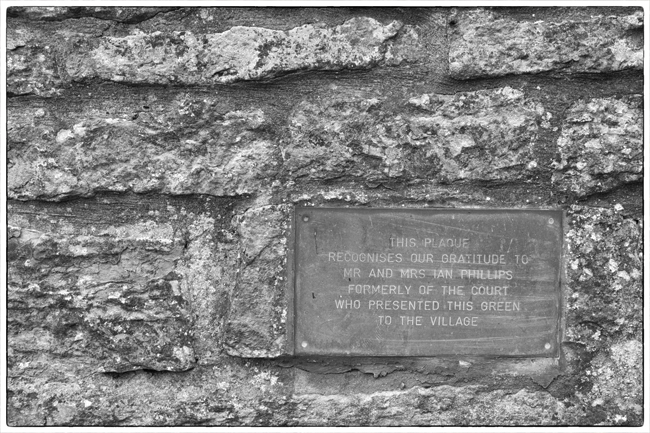

While Godney has the place of worship, Lower Godney has the meeting place. This is where the Village Hall is located, as well as the local pub, The Sheppey Inn (named after the river that runs behind it).

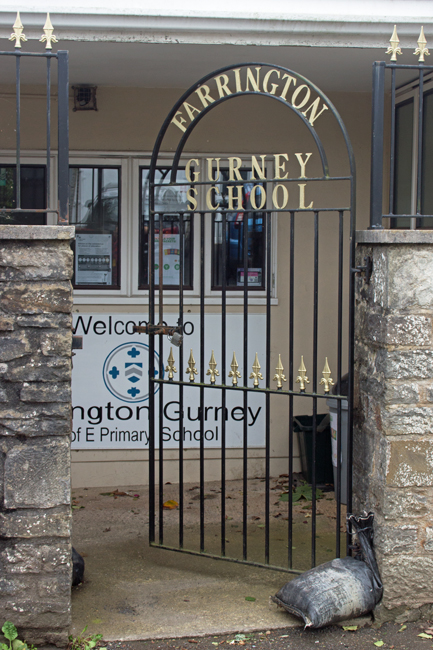

Upper Godney is today just a small stretch of houses, but it was once where the local school was located as well as the village post office. Both have now closed and are houses.

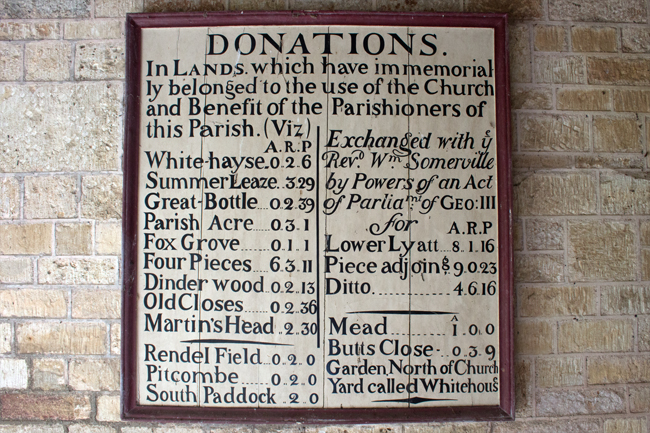

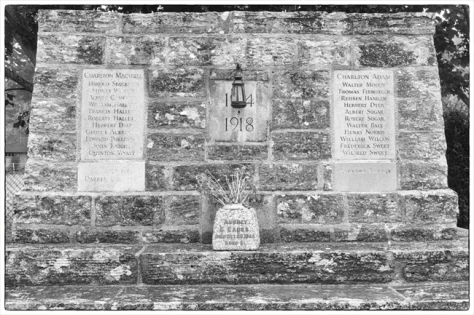

There are no war graves in Godney. However, like Dinder, it formed part of the war lines, and the landscape includes a number of pill boxes at either end.

The Godneys are surrounded by flat, drained marshland and the natural ditches formed the basis of tank defences during the Second World War. These were supplemented with a purpose-built anti-tank ditch around the village, while bridges in the area were prepared for demolition at short notice.

The Godneys are a great place for walking and cycling, particularly as the ground is so level. The views south to Glastonbury Tor and north to the Mendips are well worth it.