In a world where we are badgered to wash our hands for twenty seconds, now is the time to care and protect.

Mask yourself and protect others.

Nature will win out either way, so what is the harm?

In a world where we are badgered to wash our hands for twenty seconds, now is the time to care and protect.

Mask yourself and protect others.

Nature will win out either way, so what is the harm?

Relish in the fruits of your labour.

You have earned this reward, so sit back, relax, and take pleasure in what has been achieved.

You deserve this.

Samuel Cook was born in Bedfordshire, the eldest of two children to Alfred and Phoebe Cook.

Alfred was a forester, which saw the family move around the country; the 1881 census found them living in Rutland, ten years later the family was recorded in Northamptonshire and by the 1911 census, they were in Dorset.

Samuel was quick to follow in his father’s footsteps, supporting his mother and sister after Alfred died in 1906.

The was was underway when Samuel was called up. His service records show that he enlisted on 11th December 1915. His fitness seemed to have determined the path his military career would take.

Initially Private Cook was classified as C1 (free from serious organic diseases and able to serve in garrisons at home, able to walk 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well), but was upgraded to B2 within six months. This identified that he was free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on lines of communication in France, or in garrisons in the tropics and able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes.

Samuel was first enrolled in 13th (Works) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, before being transferred to the 311th (HS) Labour Company in Plymouth.

Private Cook was one of the thousands of soldiers who contracted influenza and subsequently died of pneumonia on 1st November 1918.

There seems to be some dispute over how and when Samuel fell ill. A request for a detailed medical report was sent, “as he appeared to have contracted the disease from which he died whilst on leave for the purpose of getting married”. The same request confirms that he was never admitted to hospital while in the company. (There are no records oh Samuel having married, so I am assuming that his leave may have been for wedding preparations, of normal leave.)

The report came back confirming that he has died from “pneumonia complicating influenza which was contracted whilst on service at Beaulieu”.

However and wherever it happened, the disease claimed Private Samuel Cook’s life; he lies at rest in Sherborne Cemetery, Dorset.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Born in Lancashire in 1877, Nicholas Leadbetter was the eldest of the four children of fisherman and merchant Isaac and his wife Elizabeth. He was quick to follow in his father’s line of work and set up his own fish shop in St Anne’s-on-the-Sea (nowadays known as Lytham St Anne’s).

Nicholas married Alice Griffiths in 1900, and their first child – Isaac – was born that Christmas.

Living near the station in Lytham, the young couple took on boarders to supplement Nicholas’ work. By the time of the 1901 census they had Dionysius Howarth, a chemist’s assistant, and Edgar Charles Randolph Jones, a grocer’s assistant, staying with them.

The Leadbetters don’t appear on the 1911 census, but from later records it is evident that they moved from Lancashire to the South West, where Nicholas ran a fish, game and poultry store in Yeovil. By this time, they were a family of four, as a daughter – Alice – was born in 1906.

Nicholas moved his family across the border to Sherborne, where he continued to ply his trade as a fishmonger and poultry dealer.

War broke out and, at the age of 39, he enlisted in the fledgling Royal Air Force, serving in France for the remainder of the fighting.

Serjeant Nicholas Leadbetter was demobbed in February 1919 and returned home to his family on Valentine’s Day. A local newspaper picks up his story from there.

He was feeling unwell at the time and immediately went to bed. Double pneumonia set in, and, despite the best medical aid, he passed away on Tuesday, leaving a widow, one son, and one daughter to mourn their loss.

Western Gazette: Friday 21st February 1919.

Serjeant Leadbetter’s funeral was a fitting one:

[It] was of military character, members of the Sherborne detachment of the 1st Volunteer Battalion Dorset Regiment being present. The coffin, which was covered with the Union Jack, was borne by members of the detachment, and at the Cemetery a firing party fired three volleys over the grave, and the buglers of the Church Lads’ Brigade sounded the last post.

There were many floral tributes. Mrs Leadbetter wishes to return thanks for the many letters of sympathy received from kind friends, and which she finds it impossible to answer individually.

Western Gazette: Friday 28th February 1919.

Serjeant Nicholas Leadbetter lies at peace in Sherborne Cemetery.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Things sometimes seem vast and impossible to overcome.

Break your challenge down into manageable chunks.

Tick off one part at a time and your journey will seem less daunting.

As mentioned in the previous post, it is often a challenge to find details of the fallen soldiers whose graves pepper the churchyards of the UK.

Sadly, Gunner Thomas Kelly is one of those names lost to time.

Born in 1893, he lived in Alsager, Cheshire and enlisted in the Royal Field Artillery. Wounded, he was moved to the Yeatman Hospital in Sherborne, Dorset, but died of his wounds on 11th January 1918.

He was buried in the town’s cemetery on 16th January 1918; he was just 25.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Frederick Brooks was born in the spring of 1897, the ninth of eleven children to Stephen and Grace Brooks. Stephen worked as a woodsman in Bredhurst, Kent, a trade his eldest sons followed him into.

Frederick’s service records show that, when he enlisted in nearby Rainham, he was working as a fence maker. He was 5ft 6ins (168cm) tall, weighed 143lbs (65kg) and had fair physical development. He joined up in September 1915 and was assigned to the 2/1 Company Kent Royal Garrison Artillery.

Gunner Brooks’ early service was on home soil as part of the Territorial Force. However, he was transferred overseas as part of the British Expeditionary Force on 10th March 1917, where he served for nearly two years.

Frederick fell ill in January 1919, and was brought back to the UK for treatment. He was admitted to the Weir Red Cross Hospital in Balham, London, with bronchial pneumonia. He succumbed to heart failure just a few days later, on 4th February 1919. He was just 21 years old.

Gunner Frederick Brooks lies at rest in a peaceful corner of the secluded graveyard of St Peter’s Church in his home village of Bredhurst.

Frederick’s life throws a couple of coincidences my way. I used to live within spitting distance of his village, Bredhurst, and, indeed, have drive past his family home countless times. I also happened to have been born in the same hospital – the Weir in Balham – where Frederick had passed away 53 years earlier.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

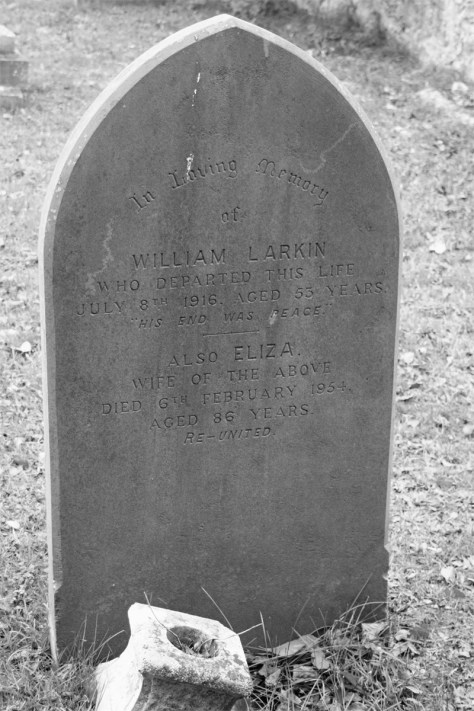

William Larkin was born in 1863, the eldest son of Alfred and Frances Larkin from Cranbrook in Kent.

He disappears off the radar for a few censuses – there are too many variations on his surname to identify exactly where he was on the 1881 and 1891 documents.

From later documents, however, we can identify that he married Eliza in around 1886; the couple had no children. By the 1901 censes the couple were living to the north of Maidstone; ten years later, they were running the Fox & Goose pub in Weavering, Kent.

Private Larkin’s military service is also lacking in documentation, but some information can be pieced together.

Originally enlisting in the Royal West Kent Regiment, he (was) transferred over to the Royal Defence Corps, and served on home soil.

On Sunday 2nd April 1916, Lance Corporal Larkin was on guard at a gunpowder factory in Faversham, Kent. As the Ministry of Munitions reported at the time:

During the weekend a serious fire broke out in a powder factory in Kent, which led to a series of explosions in the works.

The fire, which was purely accidental, was discovered at midday and the last of the explosions took place shortly after two in the afternoon.

The approximate number of casualties is 200.

Thanet Advertiser: Saturday 8th April 1916.

William was not killed during the incident, but Boxley Parish Council (who covered the Weavering area) carried out research on the names on the village war memorial. According to that research, William “developed cancer after the ‘Faversham Powder Works’ explosion”. He died two months later, on 8th July 1916. He was 53 years of age.

Lance Corporal William Larkin lies at rest in the graveyard of St Mary & All Saints Church in Boxley, Kent.

The 1916 explosion at Faversham was the worst in the history of the British explosives industry.

At 14:20 on Sunday 2 April 1916, a huge explosion ripped through the gunpowder mill at Uplees, near Faversham, when a store of 200 tons of trinitrotoluene (TNT) was detonated following some empty sacks catching fire. The TNT and ammonium nitrate (used to manufacture amatol) had exploded.

The weather might have contributed to the start of the fire. The previous month had been wet but had ended with a short dry spell so that by that weekend the weather was “glorious”, providing perfect conditions for heat-generated combustion.

Although not the first such disaster at Faversham’s historic munitions works, the April 1916 blast is recorded as “the worst ever in the history of the UK explosives industry”, and yet the full picture is still somewhat confused.

The reason for the fire is uncertain. And considering the quantity of explosive chemicals stored at the works – with one report indicating that a further 3,000 tons remained in nearby sheds unaffected – it is remarkable, and a tribute to those who struggled against the fire, that so much of the nation’s munitions were prevented from contributing further to the catastrophe.

(Information about the explosion drawn from Wikipedia.)

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Thomas Charles Holloway was born in Chatham, Kent in 1893. The fourth of five children, his parents were Joseph, a domestic coachman, and Caroline Holloway.

By the time of the 1911 census, Thomas had left school and was working in a corn warehouse.

Thomas presented a bit of a challenge when I was researching his history.

His military records show that he enlisted on 31st December 1914, signing up to the Royal Field Artillery. However, Gunner Holloway’s service records show that he was posted on 9th January 1915, before being discharged as medically unfit just a week later. The records confirm that he served for 16 days.

The medical attestation states that he was discharged because of cardiac dilation and hypertrophy, a systolic murmur and dyspnoea, all heart-related conditions.

Despite only serving for just over a fortnight, he was afforded a Commonwealth War Grave when he died.

Searching the local newspapers of the time, a bigger story was unveiled.

The death of Bombardier Thomas Holloway, aged 24, of the RFA… occurred in a hospital at Cambridge. He was kicked by a horse in the course of his training, nearly two years ago, and had practically been on the sick list ever since. On recovering from the effects of the accident, he was seized with spotted fever at Seal, and ultimately succumbed to paralysis of the brain.

East Kent Gazette: Saturday 21st July 1917

The discrepancies between the original discharge and the newspaper report are intriguing. Either way, this was a young life cut far too short: he was 24 years old.

Gunner Thomas Holloway lies at rest in St Margaret’s Churchyard, in his home town of Rainham in Kent.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Time is not on our side; there is no way to stop it or slow it down.

Life is short, use it wisely.

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....