Respect the old traditions.

They got us to where we are and can teach us where to go from here.

You are who you are because of those that went before, and will be the reason those that follow will be how they will be.

Respect the old traditions.

They got us to where we are and can teach us where to go from here.

You are who you are because of those that went before, and will be the reason those that follow will be how they will be.

Build a bank of memories to look back on.

Reflections of times past can help pull you through the dark times.

Keep those memories to warm you when times are tough.

Sidney Ralph Pragnell was the eldest of two children of Edward and Ellen Pragnell. Edward grew up in Sherborne, before moving to London to work as a chef; he found employment as a cook in an officer’s mess, which took him and his wife first to Ireland – where Sidney was born – and then to the barracks at Aldershot.

By the time of the 1911 census, Edward had brought his family back to Dorset, and was running the Half Moon Hotel, opposite the Abbey in Sherborne. Sidney, aged 12, was still at school.

When war broke out, Sidney was eager to play his part, even though he was underage. An article in the local newspaper highlights his keenness and how he progressed.

When war broke out, he was keen to serve his country and joined every local organisation his age would allow him to. He was an early member of the Sherborne VTC and Red Cross Detachment, and was actually the youngest member of the Volunteers to wear the uniform. Whilst still under age, he enlisted in the Royal Naval Division at the Crystal Palace and after a period of training was drafted as a qualified naval gunner to a merchant steamer carrying His Majesty’s mails and in this capacity went practically round the world. In February [1919] he joined the RNAS and after some air training in England went to France to an air station, where he passed all the tests with honours and gained the ‘wings’ of the qualified pilot. Lieutenant Pragnell then decided to go in for scouting and came back to England for advanced training in the special flying necessary for this qualification and it was whilst engaged in this that he met with the accident which resulted in his death.

Western Chronicle: Friday 16th August 1918.

The esteem in which Second Lieutenant Pragnell was held continues in the article, which quotes the condolence letter sent to his parents by his commander, Major Kelly.

It is with deep regret that I have to write you of the death of your son, Second-Lieutenant SR Pragnell. Your boy was one of the keenest young officers I have ever had under my command and was extremely popular with us all and his place will be extremely hard to fill.

The service can ill afford to lose officers of the type of which Lieutenant Pragnell was an excellent example and it seems such a pity this promising career was cut short when he had practically finished his training. May I convey the heartfelt sympathy of all officers and men in my command to you in this your hour of sorrow.

Western Chronical: Friday 16th August 1918.

What I find most interesting about this article is that the letter from Major Kelly detail how Edward and Ellen’s son died, and this this too is quoted by the newspaper.

Your son had been sent up to practice formation flying and was flying around the aerodrome at about 500 feet with his engine throttled down waiting for his instruction to ‘take off’. Whiles waiting your boy tried to turn when his machine had little forward speed. This caused him to ‘stall’ and spin and from this low altitude he had no chance to recover control and his machine fell to earth just on the edge of the aerodrome and was completely wrecked. A doctor was there within a minute, but your boy had been killed instantaneously.

Western Chronicle: Friday 16th August 1918.

Further research shows that the aerodrome Second Lieutenant Pragnell was training at was RAF Freiston in Lincolnshire, which had been designated Number 4 Fighting School with the specific task of training pilots for fighting scout squadrons. He had been flying a Sopwith Camel when he died.

Second Lieutenant Sidney Ralph Pragnell lies at rest in the cemetery of his Dorset home, Sherborne.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Born in Lancashire in 1877, Nicholas Leadbetter was the eldest of the four children of fisherman and merchant Isaac and his wife Elizabeth. He was quick to follow in his father’s line of work and set up his own fish shop in St Anne’s-on-the-Sea (nowadays known as Lytham St Anne’s).

Nicholas married Alice Griffiths in 1900, and their first child – Isaac – was born that Christmas.

Living near the station in Lytham, the young couple took on boarders to supplement Nicholas’ work. By the time of the 1901 census they had Dionysius Howarth, a chemist’s assistant, and Edgar Charles Randolph Jones, a grocer’s assistant, staying with them.

The Leadbetters don’t appear on the 1911 census, but from later records it is evident that they moved from Lancashire to the South West, where Nicholas ran a fish, game and poultry store in Yeovil. By this time, they were a family of four, as a daughter – Alice – was born in 1906.

Nicholas moved his family across the border to Sherborne, where he continued to ply his trade as a fishmonger and poultry dealer.

War broke out and, at the age of 39, he enlisted in the fledgling Royal Air Force, serving in France for the remainder of the fighting.

Serjeant Nicholas Leadbetter was demobbed in February 1919 and returned home to his family on Valentine’s Day. A local newspaper picks up his story from there.

He was feeling unwell at the time and immediately went to bed. Double pneumonia set in, and, despite the best medical aid, he passed away on Tuesday, leaving a widow, one son, and one daughter to mourn their loss.

Western Gazette: Friday 21st February 1919.

Serjeant Leadbetter’s funeral was a fitting one:

[It] was of military character, members of the Sherborne detachment of the 1st Volunteer Battalion Dorset Regiment being present. The coffin, which was covered with the Union Jack, was borne by members of the detachment, and at the Cemetery a firing party fired three volleys over the grave, and the buglers of the Church Lads’ Brigade sounded the last post.

There were many floral tributes. Mrs Leadbetter wishes to return thanks for the many letters of sympathy received from kind friends, and which she finds it impossible to answer individually.

Western Gazette: Friday 28th February 1919.

Serjeant Nicholas Leadbetter lies at peace in Sherborne Cemetery.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Reuben Victor Stanley Hadlow was born in the spring of 1898. He was one of thirteen children to John Charles Tarpe Hadlow and his wife Gertrude, publicans at the Star pub in Whitstable, Kent.

When war broke out, Reuben was working as a blacksmith; he enlisted in the army in the summer of 1914, serving on the home front.

In February 1916 Private Hadlow transferred to the Royal Flying Corps as a Air Mechanic 2nd Class, and was assigned to the 65 Training Squadron in Croydon. He was promoted to Air Mechanic 1st Class six months later.

When the RFC became the Royal Air Force, Air Mechanic Hadlow moved across to the new institution. He moved to support 156 Squadron in November 1918, then the 35 Training Depot Station shortly after.

Air Mechanic Hadlow contracted phthisis (tuberculosis) towards the end of that year, which led to his being discharged from the RAF on 22nd January 1919.

Reuben’s health did not recover after returning home – his parents were running the King’s Arms pub in Boxley near Maidstone by this point. He passed away on 17th September 1919, aged twenty-one.

He lies at rest in the churchyard of St Mary and All Saints, in his parent’s village.

Poignantly, his gravestone is not a traditional war grave. Instead it states that he died “after a painful illness and serving his country 4 1/2 years”.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

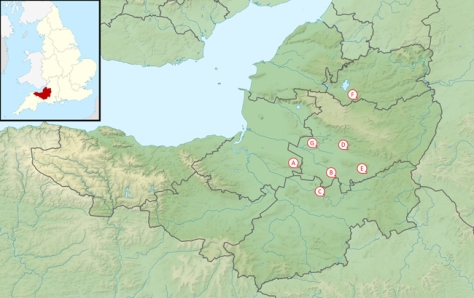

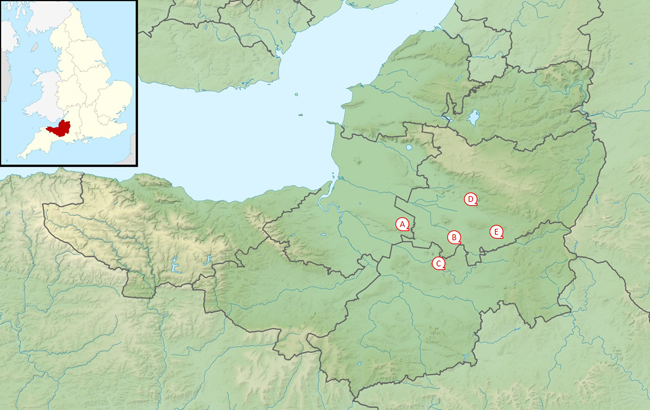

As history moves on, it seems there were two main routes for villages to take. As we have seen, the first is to thrive, then to settle quietly into the background and become a quintessential English village, as with Haselbury Plucknett and Milverton (see previous posts).

The second option is not as positive, and this has been the route taken by the next village on our Somerset journey, Othery.

Sitting on the crossroads of the main roads between Bridgewater and Langport, Glastonbury/Street and Taunton, Othery once thrived as a stopping off point on the long journeys across sometimes threatening terrain.

The Other Island sits 82ft (20m) above the surrounding moorland of the River Parrett, and so proved a good resting point for horses, carriages and passengers alike. For a population of around 500 people, this was once a bustling place, boasting three pubs, a post office, village store and bakery.

Sadly, the village has not thrived, and is nowadays more of a cut through, one of those places you see the road sign for, before slowing to 30mph and impatiently waiting for the national speed limit sign to come into view.

The buildings on the main road seem a little tired, once white frontages sullied by the dirt and grime of passing juggernauts. The signs outside the one remaining public house – the London Inn – almost beg you to stop, whether for a Sunday carvery or to watch weekend football matches on the huge TV screens.

(I admit the scaffolding does little to show the pub in its best light.)

But the fact of the matter is that, where once it would have had regular bookings, you can’t help feeling that this is very much a locals’ pub, whose inhabitants have set places at the bar and engraved tankards.

One glimmer of hope is that the the bakery seems to attract a lot of support. Again, it was closed when I stopped off here late one afternoon, but whenever I have driven through Othery before, there has tended to be a queue of people outside, and this gives a hint at a sense of community that the commuter doesn’t get to see.

The community sense continues with the school sign too; a typical redbrick Victorian building enticing children in. Another sign of things changing is that, where this was once Othery Village School, it has now merged with neighbouring Middlezoy; families move out of the smaller villages, school numbers drop, changes take place to help support struggling services.

Move away from the main road, though, and you can see tantalising hints of what Othery once was, and probably still would be, had its position on the crossroads not been the main function of its existence.

North Lane is a much quieter affair than the main road. In between the mid-20th Century houses sit more stately structures, hidden behind high walls to shelter them from passing traffic.

St Michael’s Church stands proud above the village, helping direct the wayward and lost to a better life. You get the feeling, however, that locals stay behind their high walls more than they used to, something sadly echoed across rural Britain more than one might care to admit.

I am painting a pretty bleak picture, I know, but, while not deliberately doing the village down, this is the sense you get when exploring a place like Othery.

Where villages like North Curry once had glory, they were fortunate in their locale. Those villages that lie too short a distance from neighbouring towns have struggled in recent years, and Othery is not an exception.

Using the same stretch of road between Street and Taunton as an example, places like Walton, Greinton, Greylake, East Lyng, West Lyng and Durston have also struggled over the years.

Villages with a distinct pull, a unique selling point, like Burrowbridge on the same stretch of road, do survive, but for others it has been a struggle.

Additional housing projects have tried to rejuvenate them, but without the infrastructure to support them, the villages still die or get swallowed up by those neighbouring towns.

George Henry Stone was born in 1872, son of Milverton’s blacksmith James Stone and his wife Mary Ann. He followed in his father’s footsteps and, by the time he married Mary Florence Paul in 1894, he was also working in the forge in Milverton.

George and Mary had eight children – seven girls and one boy; by the time he signed up in 1915, he listed himself as a blacksmith.

His military records show that he was medically certified as Category B2 (suitable to serve in France, and able to walk 5 miles, see and hear sufficiently for ordinary purposes). He was assigned to the Remount Depot in Swaythling, Southhampton, which was built specifically to supply horses and mules for war service. (In the years it was operating, Swaythling processed some 400,000 animals, as well as channelling 25,000 servicemen to the Front.)

While serving George contracted pneumonia. He was treated in Netley Military Hospital, but passed away on 19th November 1918, aged 47.

Shoesmith George Henry Stone lies at peace in a quiet corner of St Michael & All Angel’s churchyard in his home village of Milverton.

The next in the A-Z is one that potentially challenges what I am looking to achieve in a list of Somerset villages as it examines what actually constitutes a village.

In England, at least, you have hamlets, villages, towns and cities.

So, why bring this up now?

Well, the issue with the next place I have visited is that technically it is not a village.

Godney has a handful of houses, a farm and a small church (Holy Trinity), but no meeting point.

It lies just to the north of Glastonbury, on a small rise overlooking the River Sheppey.

Why am I including Godney in the A-Z, then? Well, on the other side of the river are two other hamlets – Upper Godney and Lower Godney – and between the three of them, they meet all of the requirements of a village.

So, then, I am looking at The Godneys, not just Godney itself. (Okay, it’s a bit of a stretch, but they’re nice places!)

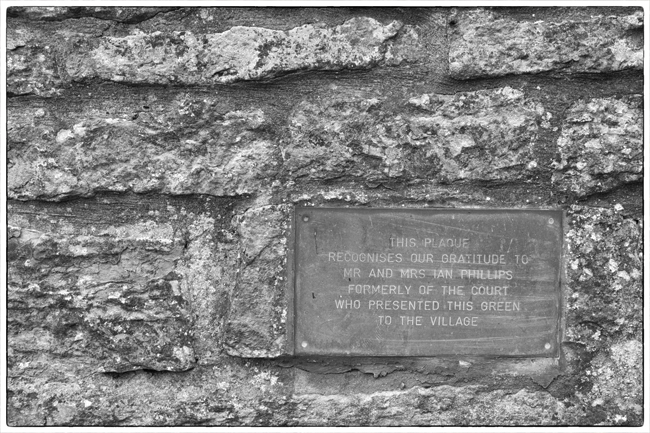

While Godney has the place of worship, Lower Godney has the meeting place. This is where the Village Hall is located, as well as the local pub, The Sheppey Inn (named after the river that runs behind it).

Upper Godney is today just a small stretch of houses, but it was once where the local school was located as well as the village post office. Both have now closed and are houses.

There are no war graves in Godney. However, like Dinder, it formed part of the war lines, and the landscape includes a number of pill boxes at either end.

The Godneys are surrounded by flat, drained marshland and the natural ditches formed the basis of tank defences during the Second World War. These were supplemented with a purpose-built anti-tank ditch around the village, while bridges in the area were prepared for demolition at short notice.

The Godneys are a great place for walking and cycling, particularly as the ground is so level. The views south to Glastonbury Tor and north to the Mendips are well worth it.

A hop and a skip away from Dinder is a bit of a jolt; the population of Evercreech is ten times the size, and you do notice it.

Just to the south of Shepton Mallet, this has the potential to be a bustling place, although the day I visited was a typically English summer, with heavy showers, so it was quieter than it could have been.

The centre of the village holds onto its Norman roots – Evrecriz was mentioned in the Doomsday book – and the buildings are old stone cottages, with the occasional larger manor thrown in.

The church, however, is one of the things that drew me to choosing this as my ‘E’ village. The renowned twentieth century architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner said than it has one of the finest Somerset-style towers in the county, but it is the mysterious clock that interested me.

The face of the clock has no 10 on it (or no X, in Roman numerals). Instead, the numbers go 9 – 11 – 12 – 12 (IX – XI – XII – XII).

Local rumour suggests that the person who paid for the clock to be made was instructed by his wife that he had to be home from the pub by 10 o’clock. Therefore, he ensured that the 10 o’clock numeral (X) was missing from the clock face.

While the village is a large one – with a population of nearly 2,500 – it is very easy to get into the open countryside.

Walk past the Bell Inn, one of Evercreech’s three pubs, and you find yourself crossing open fields to reach the village’s cemetery.

A small graveyard, but still in regular use, this holds a history of its own.

There is a war memorial to those who fell in both World Wars, while there are four war graves to those whose remains were able to be buried on English soil. Four stories, which I’ll explore in later posts.

An A-Z of Somerset Villages include:

One of the things I have found since moving down to Somerset how different the place names are from back in the south east of England. For every Yeovil there is a Kingsbury Epicopi, for every Bridgwater, a Chiltern Cantelo. The etymology of these place names holds a constant fascination for me, and is another reason I have set out to explore the local area more.

So it is that, on reaching the letter C in my quest, that I choose an unusually named village to photograph.

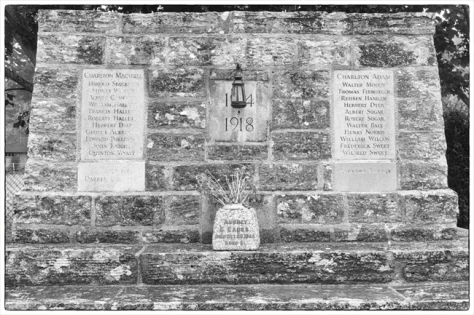

Charlton Mackrell lies midway between Glastonbury and Yeovil, on Bull Brook, a tributary of the River Cary. It shares its name with the neighbouring village – the similarly named Charlton Adam – and, like Baltonsborough, has a population of around 1000 inhabitants.

The names of the villages can be traced back centuries – Charlton comes from the Saxon word for “farmstead of the freemen”. Adam can be pinpointed to the local FitzAdam family who once lived there. Mackrell is less easy to pin down, but it is likely to have similar origins.

Certainly manorial buildings rule over the village in the way they tend to do; large houses and mysterious gated entrances can be found all over. The local church – Saint Mary The Virgin – sits right next to, and is obviously connected to, one of the larger properties (after all, manorial families often built religious buildings out of their own money to show their devotion to God, which just happened to help them control the local population).

The Charltons also suffered at the hands of Dr Beeching; the railway station closed in 1962, along with the other six stations between Castle Cary and Taunton. Three railway bridges survive, however, the lowest of which is only 2.7m (8’9″) high.

The villages’ war memorial is, unusually, not at the heart of things. It is, instead, nestled in a fork in the road joining the Charltons. Sadly, it only serves to highlight that, even in the depths of the Somerset countryside, tight knit communities were in no way immune to the ravages of war.

There are, thankfully, only eleven names of the lost under each of the villages, but given that the combined population of the two villages at the time was around 600, these twenty-two fallen represented an unthinkable loss for those left behind.

Two of the men on the Mackrell side of the memorial are buried in St Mary’s churchyard. If you have followed my previous CKPonderings blog, you will know that the history and stories behind those who fell during the Great War fascinate me.

Private Quinton Charles Wyatt was born in the Gloucestershire town of Northleach in 1893 to William and Elizabeth. His mother died when he was a toddler and, by the time war was declared, Quinton was working as a farm labourer and waggoner.

He joined the 8th Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment on 22nd November 1915. He was posted to France four months later, but medically discharged from the Army on Boxing Day 1917.

Private Wyatt died in Charlton Mackrell on 11th November 1918 – Armistice Day – and buried in St Mary’s churchyard.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/203685657

Private Roberts Pretoria Hallett was born in the summer of 1900, to Frank – a shepherd from Charlton Adam – and Emily, who came from Charlton Mackrell. Roberts (the correct spelling) was the youngest of eleven children.

Roberts was just twelve when his father died, and, when war came, he enlisted in Taunton, along with his brothers, Francis and William. The Great War was not kind to Emily Hallett: her son William died while fighting in India in 1916; Francis died in the Third Battle of Ypres in June 1917.

Roberts was assigned to the 5th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment; while I’ve been unable to identify exactly when he saw battle, by the last year of the war he would have been involved in the fighting in northern Italy.

What we can say for certainty was that is was shipped home at some point towards the end of the war, and died – presumably of his injuries – in Newcastle-upon-Tyne on 16th October 1918.

William Hallett was buried in India, Francis in Belgium. Private Roberts Hallett, therefore, is the only one of the three brothers to be buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s in his birthplace of Charlton Mackrell.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/203685613

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....