#178

Okay, so this seems to be a thing now…

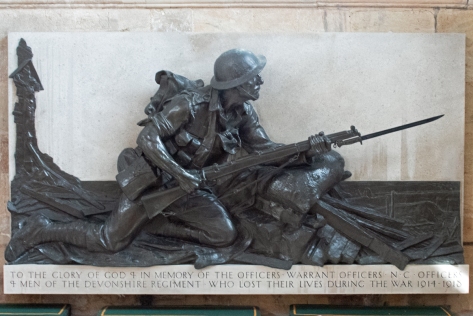

So, after a year of combining my love of photography with those of genealogy and social history, my first book (eek!) is now available to buy.

hose gravestones has a story connected to it, a story of family and of tragedy, a story of life on the battlefield and of love on the home front.

These were men and women from over sixty regiments, drawn to the cause from all corners of the Empire. They were wounded in battle or succumbed to disease, they were caught up in accidents or died at their own hands. These were soldiers of all ranks, age and class; brave pioneers of aviation; people seeking adventure on the high seas. Above all these were hopes, dreams and aspirations lost, cut tragically short for King and Country.

This book aims to shed light on the servicemen and women behind the names on these gravestones, to bring those long-forgotten names to life again, a century after they were lost.”

Available as an eBook and paperback, you can find it on Amazon by clicking on the image above.

I’ve been a keen photographer for years now, as anyone who had followed the CKPonderings or CKPonderingsToo blogs will know. What began as a hobby quickly became an obsession, and there was rarely a time that I would venture out without my camera.

Given the number of photographs I took, the subject range became vast, and seeing the world in a slightly different way helped me view things in ways that others found a bit odd. (“Why was I taking a photograph of those wires hanging from the wall?” for example.)

With a move to Somerset coinciding with life coming to a halt as pandemic swept the world, I used the once-a-day forays out of doors to explore the villages around me. Part of this photographic exploration naturally included the local church, and the atmosphere of the graves and tranquillity the churchyard instilled was a natural draw for my eye.

One of my other passions in recent years has been collecting – rescuing – old and antique photographs, the idea that these were people whose lives were fogged in anonymity and lost to time. I love the social history that these studio portraits convey, and am saddened that nobody will ever know whose these people were.

The social history side of my brain kicked in once more when I was wandering around the Somerset graveyards. The names inscribed on the headstones represent lives that again, have been lost to time, and what drew me even more was the thought that the names of the soldiers, sailors, airmen and medical staff that featured on the Commonwealth War Graves in some of these churchyards may, again, be lost to time.

So, as part of my research into the story of the villages I visited, I began to investigate the names on these gravestones, to see how much of these people’s lives could be recovered or reconstructed. There are more than 800,000 War Graves across the UK and more than 800 of those can be found in over 240 cemeteries and churchyards across Somerset. Each of the names on those gravestones has a story connected to it, a story of family and of tragedy, a story of life on the battlefield and of love on the home front.

The names on these graves represent men and women from over sixty regiments, drawn to the cause from all corners of the Empire. They were wounded in battle or succumbed to disease, they were caught up in accidents or died at their own hands. These were soldiers of all ranks, age and class; brave pioneers of aviation; people seeking adventure on the high seas. Above all these were hopes, dreams and aspirations lost, cut tragically short for King and Country.

These were people like Guardsman Harold Dummett from the village of Kingsdon, who enlisted in the the Coldstream Guards, but died of pleurisy and pneumonia in 1919 at the age of just 19 years old.

These were soldiers like Rifleman Harry Trevetic of the King’s Royal Rifles. Born in Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire, he served in the Boer Wars and acted as batman to a Captain Makins.

Makins was injured on the Western Front, but Harry carried him to the nearest field hospital, then stayed with him there and returned to England as his assistant while he recovered.

Makins received his orders to return to the Front, but the idea of returning there horrified Rifleman Trevetic who chose to take his own life, rather than return to the terrors that awaited.

There was Second Lieutenant Sidney Pragnell from Sherborne in Dorset, who was so keen to play his part, he enlisted in the Royal Navy while under age.

He moved to the Royal Naval Air Service, which became the Royal Air Force, and was killed in a flying accident in August 1918.

Read more about Second Lieutenant Pragnell.

There was Staff Nurse Dorothy Stacey, also from Sherborne in Dorset who, because she came from a ‘good family’ was able to join the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserves.

After time spent tending to the troops returning wounded and injured from the Front, she fell ill, probably contracting one of the many conditions she had found herself treating, and died at the tender age of just 25 years old.

Read about Staff Nurse Stacey.

There was Private John Russell, who was hit by a motor car while guarding his camp. Just 19 years of age, he was buried in his home village of Meare, near Glastonbury.

The driver, Vera Coysh, went on to become an author of romantic novels.

Read more about Private Russell.

I am drawn to these sad and tragic tales, but also moved by the seeming randomness of the way life was taken.

The sleepy village of Lydeard St Lawrence has in its churchyard the graves of three brothers, William, Stephen and Ernest Rawle, all of whom died for their cause, leaving their other sibling, Edward, the only one to return from the European battlefields.

Read more about William Rawle, Stephen Rawle and Ernest Rawle.

In Yeovil Cemetery, on the other hand, lies Joseph Dodge, one of seven brothers to fight in the conflict, and the only one of the seven not to survive.

Read more about the life of Private Dodge.

There are countless stories to be told, and it is a privilege to be able to share some of these on the Death and Service website.

One hundred tales of the fallen of World War One.

One hundred tales of pandemics, battlefield wounds, accidental shootings, car crashes, drownings, suicides, tram accidents and plane crashes.

One hundred tales of soldiers, sailors, airmen and nursing staff, from the United Kingdom, Canada, South Africa and the West Indies.

One hundred stories behind the names on the gravestones.

Let their stories not be forgotten.

Learn more at the CKPonderingsCWG blog.

William Crossan was born in 1892 in Ballinamore, Ireland. He was the fourth of five children to Patrick and Catherine Crossan.

William disappears from the 1911 Census or Ireland, but has joined the Irish Guards by the time war broke out.

Guardsman Crossan’s battalion was involved in the Battle of Mons, but it was during the fighting at Ypres that he was injured.

Shipped back to the UK for treatment, William passed away on 2nd November 1914. I am assuming that this was at one of the Red Cross Hospitals in the Sherborne area, as this is where he was buried.

Guardsman William Crossan lies at rest in Sherborne Cemetery.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Edward (Teddy) Lewsley was born in 1894, the ninth of twelve children to James and Charlotte Lewsley from London.

James had worked with horses, and become a cab driver at the turn of the century; Edward started as a general labourer on finishing school.

Edward’s military history is a little vague. From his gravestone, we know that he joined the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and was in the 1st Battalion. The battalion fought at the Battles of Mons, Marne and Messines.

In the spring of 1915, Edward’s battalion fought in the Second Battle of Ypres and, given the timing, it seems likely that he was involved.

Whether he was on the Western Front or stationed in the UK, Private Lewsley was admitted to the Red Cross Hospital in Sherborne, where he passed away on 30th May 1915.

One of Edward’s brothers also enlisted in the Light Infantry.

Daniel Lewsley first joined the East Surrey Regiment in 1909 and continued through to 1928. This included a stint as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Sidney Ralph Pragnell was the eldest of two children of Edward and Ellen Pragnell. Edward grew up in Sherborne, before moving to London to work as a chef; he found employment as a cook in an officer’s mess, which took him and his wife first to Ireland – where Sidney was born – and then to the barracks at Aldershot.

By the time of the 1911 census, Edward had brought his family back to Dorset, and was running the Half Moon Hotel, opposite the Abbey in Sherborne. Sidney, aged 12, was still at school.

When war broke out, Sidney was eager to play his part, even though he was underage. An article in the local newspaper highlights his keenness and how he progressed.

When war broke out, he was keen to serve his country and joined every local organisation his age would allow him to. He was an early member of the Sherborne VTC and Red Cross Detachment, and was actually the youngest member of the Volunteers to wear the uniform. Whilst still under age, he enlisted in the Royal Naval Division at the Crystal Palace and after a period of training was drafted as a qualified naval gunner to a merchant steamer carrying His Majesty’s mails and in this capacity went practically round the world. In February [1919] he joined the RNAS and after some air training in England went to France to an air station, where he passed all the tests with honours and gained the ‘wings’ of the qualified pilot. Lieutenant Pragnell then decided to go in for scouting and came back to England for advanced training in the special flying necessary for this qualification and it was whilst engaged in this that he met with the accident which resulted in his death.

Western Chronicle: Friday 16th August 1918.

The esteem in which Second Lieutenant Pragnell was held continues in the article, which quotes the condolence letter sent to his parents by his commander, Major Kelly.

It is with deep regret that I have to write you of the death of your son, Second-Lieutenant SR Pragnell. Your boy was one of the keenest young officers I have ever had under my command and was extremely popular with us all and his place will be extremely hard to fill.

The service can ill afford to lose officers of the type of which Lieutenant Pragnell was an excellent example and it seems such a pity this promising career was cut short when he had practically finished his training. May I convey the heartfelt sympathy of all officers and men in my command to you in this your hour of sorrow.

Western Chronical: Friday 16th August 1918.

What I find most interesting about this article is that the letter from Major Kelly detail how Edward and Ellen’s son died, and this this too is quoted by the newspaper.

Your son had been sent up to practice formation flying and was flying around the aerodrome at about 500 feet with his engine throttled down waiting for his instruction to ‘take off’. Whiles waiting your boy tried to turn when his machine had little forward speed. This caused him to ‘stall’ and spin and from this low altitude he had no chance to recover control and his machine fell to earth just on the edge of the aerodrome and was completely wrecked. A doctor was there within a minute, but your boy had been killed instantaneously.

Western Chronicle: Friday 16th August 1918.

Further research shows that the aerodrome Second Lieutenant Pragnell was training at was RAF Freiston in Lincolnshire, which had been designated Number 4 Fighting School with the specific task of training pilots for fighting scout squadrons. He had been flying a Sopwith Camel when he died.

Second Lieutenant Sidney Ralph Pragnell lies at rest in the cemetery of his Dorset home, Sherborne.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Sidney Herbert Stagg was born in 1901. The eldest child of bootmaker Sidney Stagg and his wife Frances, Sidney Jr was too young to fight in the when war broke out.

He enlisted in the Royal Navy at the beginning of 1919, and was assigned to HMS Powerful, a training vessel based in Plymouth.

Boy Petty Officer Stagg’s time in the navy was heartbreakingly short. Within a few weeks he had contracted pneumonia and succumbed to the disease on 27th February 1919. He was just 17 years old, and had been in service for 36 days.

The Western Gazette reported on his funeral:

[He] left Sherborne just over a month ago to join the Royal Navy, a career for which he had expressed a great liking, and was attached to HMS Powerful, being made Boy PO within a fortnight of his joining that ship. A short time afterwards he contracted influenza, and pneumonia supervening, he died on Thursday at the Royal Naval Hospital, at Plymouth.

A service was held in the Congregational Church, and sontinued at the graveside, where three volleys were fired by a firing party of the Volunteers [the Sherborne Detachment 1st Volunteer Battalion, Dorset Regiment], and buglers sounded the last post. The Rev. W Melville Harris (uncle of the deceased) officiated, and the principal mourners were Mr Stagg (father), Miss Joyce Stagg (sister), Mr H Hounsell (uncle), and members of the business establishment.

Western Gazette: Friday 7th March 1919.

Sidney Herbert Stagg lies at peace in the cemetery in his home town of Sherborne.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Born in 1871, Thomas Daines was one of fourteen children. His parents, Charles and Sarah, worked on a farm a few miles from Halstead in Essex.

After leaving school, Thomas followed in his father’s footsteps and, by the time of the 1891 census was also listed as an agricultural labourer. He married Kate Rawlinson in the spring of 1893, and they had two children – Matilda and Lewis – before relocating to South East London in around 1898.

The reason for the move was, more than like, job opportunities, and Thomas was soon working at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich.

Settling into their new city life, Thomas and Kate had five further children: Annie, Thomas, Alfred, Charles and Beatrice. Thomas continued as a labourer, before enlisting in the army within three months of war being declared in October 1914.

Sadly, Private Daines’ service was not be be a long one. Having suffered a bout of influenza, Thomas was admitted to a Red Cross Hospital in Sherborne, Dorset. He died of pneumonia on 22nd February 2015.

Private Thomas Daines lies at peace in the Sherborne Cemetery.

As a sad aside to Thomas and Kate’s story, their eldest son, Lewis, enlisted in the 16th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. He fought on the Western Front, and was killed in action in Pozières on 26th March 1918.

The Great War had claimed father and son.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....