Never venture into the unknown without any support.

A wingman, a back-up, a fall-back, however you choose to brand them, pick someone you can rely on to walk the path with you.

They will have your back, and you can have theirs too.

Never venture into the unknown without any support.

A wingman, a back-up, a fall-back, however you choose to brand them, pick someone you can rely on to walk the path with you.

They will have your back, and you can have theirs too.

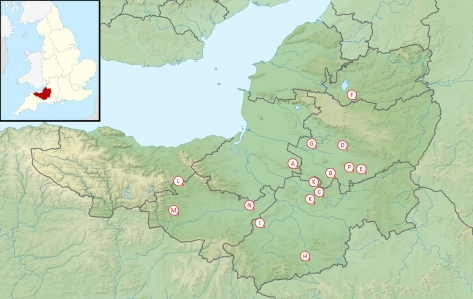

Continue up the A361 for 16 miles from Othery and you reach the surprising village of Pilton. I have driven through the village countless times over the years, and there is so much more to it than what is visible from the main road.

Situated on the top of a hill to the east on Glastonbury, the village once overlooked an inland sea that stretched to the present day Bristol Channel. This lead to the village’s original name, Pooltown, because ships were able to navigate this far inland.

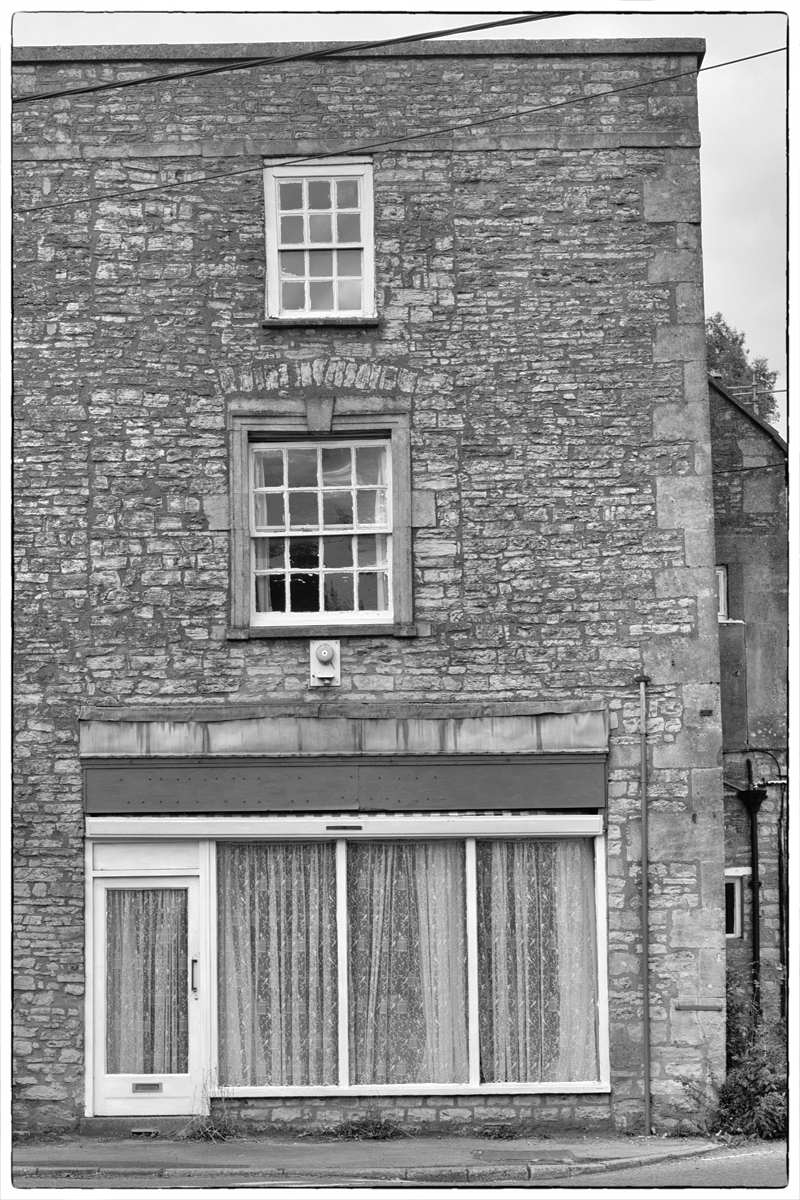

The houses in the village are old, from local stone, and really fit in with the country feel. Despite the main road, laden with juggernauts, being close by, the majority of the village is in a sheltered valley, and within a matter of metres away from the A361, it can barely be heard.

The local church is St John the Baptist, which is on the north side of the valley, has a commanding view across all Pilton. Once again, the Church’s dominance is in plain sight, and it can be seen on the skyline from most of the houses.

In the churchyard is a memorial, a grave to Sapper Percy Wright Rodgers, who fell in the First World War. More information on this young man’s life can be found on the CKPonderingsCWG blog, along with more stories of the fallen of the Great War.

To the south of the village, a tithe barn stands alone and proud. Once belonging to Glastonbury Abbey, the barn once stored local farmers’ produce, of which they gave the Abbey – the landowner – one tenth.

The barn is now a Grade 1 listed building.

In the barn’s grounds is a monument to the Land Armies of both world wars; a bench in a quiet corner of an already quiet corner of the village is perfect for contemplation.

When I first made my intention of moving to Somerset known to friend, family and colleagues, the general first reaction was usually related to the annual music festival. My stock response to this was ‘no’, and, if the mood was right, this was usually followed up by the fact that the Glastonbury Festival does not actually take place in the town of the same name.

Worthy Farm, the location of the festival, is situated just to the south of Pilton, six miles from Glastonbury. It was only called Glastonbury Festival because that was the nearest town people had heard of.

If you get the chance to make a quick pitstop from your journey to the south west, Pilton is definitely worth a visit. A genuine gem of a village, hidden in plain sight, it is also a good start and end point for a wander across the Levels or over the hilltops to Shepton Mallet.

Respect the old traditions.

They got us to where we are and can teach us where to go from here.

You are who you are because of those that went before, and will be the reason those that follow will be how they will be.

Have something you enjoy to pass the time.

Relaxation is key, so whether it is a lone project or one to enjoy with friends, take time out to do something you love.

Go fishing!

You may feel small, adrift in the whirlwind of madness that is twenty-first century living.

But be reassured that even the smallest of droplets of water nurtures the hardiest of plants.

We may all be small, but we are no less important for it.

Others may see you as strong, but you may not always feel that way.

Putting up barriers will stop people seeing the real you, but that also prevents them from helping where they can.

There is nothing wrong with frailty; it is not a weakness.

You don’t always have to put on a brave face.

William Crossan was born in 1892 in Ballinamore, Ireland. He was the fourth of five children to Patrick and Catherine Crossan.

William disappears from the 1911 Census or Ireland, but has joined the Irish Guards by the time war broke out.

Guardsman Crossan’s battalion was involved in the Battle of Mons, but it was during the fighting at Ypres that he was injured.

Shipped back to the UK for treatment, William passed away on 2nd November 1914. I am assuming that this was at one of the Red Cross Hospitals in the Sherborne area, as this is where he was buried.

Guardsman William Crossan lies at rest in Sherborne Cemetery.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Edward (Teddy) Lewsley was born in 1894, the ninth of twelve children to James and Charlotte Lewsley from London.

James had worked with horses, and become a cab driver at the turn of the century; Edward started as a general labourer on finishing school.

Edward’s military history is a little vague. From his gravestone, we know that he joined the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and was in the 1st Battalion. The battalion fought at the Battles of Mons, Marne and Messines.

In the spring of 1915, Edward’s battalion fought in the Second Battle of Ypres and, given the timing, it seems likely that he was involved.

Whether he was on the Western Front or stationed in the UK, Private Lewsley was admitted to the Red Cross Hospital in Sherborne, where he passed away on 30th May 1915.

One of Edward’s brothers also enlisted in the Light Infantry.

Daniel Lewsley first joined the East Surrey Regiment in 1909 and continued through to 1928. This included a stint as part of the British Expeditionary Force in France.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Sidney Ralph Pragnell was the eldest of two children of Edward and Ellen Pragnell. Edward grew up in Sherborne, before moving to London to work as a chef; he found employment as a cook in an officer’s mess, which took him and his wife first to Ireland – where Sidney was born – and then to the barracks at Aldershot.

By the time of the 1911 census, Edward had brought his family back to Dorset, and was running the Half Moon Hotel, opposite the Abbey in Sherborne. Sidney, aged 12, was still at school.

When war broke out, Sidney was eager to play his part, even though he was underage. An article in the local newspaper highlights his keenness and how he progressed.

When war broke out, he was keen to serve his country and joined every local organisation his age would allow him to. He was an early member of the Sherborne VTC and Red Cross Detachment, and was actually the youngest member of the Volunteers to wear the uniform. Whilst still under age, he enlisted in the Royal Naval Division at the Crystal Palace and after a period of training was drafted as a qualified naval gunner to a merchant steamer carrying His Majesty’s mails and in this capacity went practically round the world. In February [1919] he joined the RNAS and after some air training in England went to France to an air station, where he passed all the tests with honours and gained the ‘wings’ of the qualified pilot. Lieutenant Pragnell then decided to go in for scouting and came back to England for advanced training in the special flying necessary for this qualification and it was whilst engaged in this that he met with the accident which resulted in his death.

Western Chronicle: Friday 16th August 1918.

The esteem in which Second Lieutenant Pragnell was held continues in the article, which quotes the condolence letter sent to his parents by his commander, Major Kelly.

It is with deep regret that I have to write you of the death of your son, Second-Lieutenant SR Pragnell. Your boy was one of the keenest young officers I have ever had under my command and was extremely popular with us all and his place will be extremely hard to fill.

The service can ill afford to lose officers of the type of which Lieutenant Pragnell was an excellent example and it seems such a pity this promising career was cut short when he had practically finished his training. May I convey the heartfelt sympathy of all officers and men in my command to you in this your hour of sorrow.

Western Chronical: Friday 16th August 1918.

What I find most interesting about this article is that the letter from Major Kelly detail how Edward and Ellen’s son died, and this this too is quoted by the newspaper.

Your son had been sent up to practice formation flying and was flying around the aerodrome at about 500 feet with his engine throttled down waiting for his instruction to ‘take off’. Whiles waiting your boy tried to turn when his machine had little forward speed. This caused him to ‘stall’ and spin and from this low altitude he had no chance to recover control and his machine fell to earth just on the edge of the aerodrome and was completely wrecked. A doctor was there within a minute, but your boy had been killed instantaneously.

Western Chronicle: Friday 16th August 1918.

Further research shows that the aerodrome Second Lieutenant Pragnell was training at was RAF Freiston in Lincolnshire, which had been designated Number 4 Fighting School with the specific task of training pilots for fighting scout squadrons. He had been flying a Sopwith Camel when he died.

Second Lieutenant Sidney Ralph Pragnell lies at rest in the cemetery of his Dorset home, Sherborne.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Sidney Herbert Stagg was born in 1901. The eldest child of bootmaker Sidney Stagg and his wife Frances, Sidney Jr was too young to fight in the when war broke out.

He enlisted in the Royal Navy at the beginning of 1919, and was assigned to HMS Powerful, a training vessel based in Plymouth.

Boy Petty Officer Stagg’s time in the navy was heartbreakingly short. Within a few weeks he had contracted pneumonia and succumbed to the disease on 27th February 1919. He was just 17 years old, and had been in service for 36 days.

The Western Gazette reported on his funeral:

[He] left Sherborne just over a month ago to join the Royal Navy, a career for which he had expressed a great liking, and was attached to HMS Powerful, being made Boy PO within a fortnight of his joining that ship. A short time afterwards he contracted influenza, and pneumonia supervening, he died on Thursday at the Royal Naval Hospital, at Plymouth.

A service was held in the Congregational Church, and sontinued at the graveside, where three volleys were fired by a firing party of the Volunteers [the Sherborne Detachment 1st Volunteer Battalion, Dorset Regiment], and buglers sounded the last post. The Rev. W Melville Harris (uncle of the deceased) officiated, and the principal mourners were Mr Stagg (father), Miss Joyce Stagg (sister), Mr H Hounsell (uncle), and members of the business establishment.

Western Gazette: Friday 7th March 1919.

Sidney Herbert Stagg lies at peace in the cemetery in his home town of Sherborne.

For the stories of more of the fallen from the Great War, take a look at my Commonwealth War Graves page.

Commemorating the fallen of the First World War who are buried in the United Kingdom.

Looking at - and seeing - the world

Nature + Health

ART - Aesthete and other fallacies

A space to share what we learn and explore in the glorious world of providing your own produce

A journey in photography.

turning pictures into words

Finding myself through living my life for the first time or just my boring, absurd thoughts

Over fotografie en leven.

Impressions of my world....