I’ve been a keen photographer for years now, as anyone who had followed the CKPonderings or CKPonderingsToo blogs will know. What began as a hobby quickly became an obsession, and there was rarely a time that I would venture out without my camera.

Given the number of photographs I took, the subject range became vast, and seeing the world in a slightly different way helped me view things in ways that others found a bit odd. (“Why was I taking a photograph of those wires hanging from the wall?” for example.)

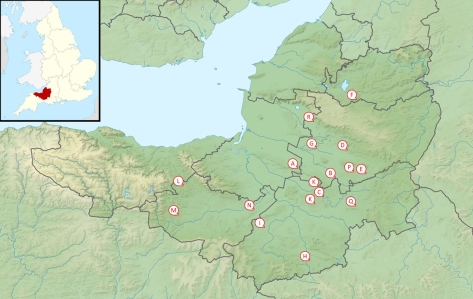

With a move to Somerset coinciding with life coming to a halt as pandemic swept the world, I used the once-a-day forays out of doors to explore the villages around me. Part of this photographic exploration naturally included the local church, and the atmosphere of the graves and tranquillity the churchyard instilled was a natural draw for my eye.

One of my other passions in recent years has been collecting – rescuing – old and antique photographs, the idea that these were people whose lives were fogged in anonymity and lost to time. I love the social history that these studio portraits convey, and am saddened that nobody will ever know whose these people were.

The social history side of my brain kicked in once more when I was wandering around the Somerset graveyards. The names inscribed on the headstones represent lives that again, have been lost to time, and what drew me even more was the thought that the names of the soldiers, sailors, airmen and medical staff that featured on the Commonwealth War Graves in some of these churchyards may, again, be lost to time.

So, as part of my research into the story of the villages I visited, I began to investigate the names on these gravestones, to see how much of these people’s lives could be recovered or reconstructed. There are more than 800,000 War Graves across the UK and more than 800 of those can be found in over 240 cemeteries and churchyards across Somerset. Each of the names on those gravestones has a story connected to it, a story of family and of tragedy, a story of life on the battlefield and of love on the home front.

The names on these graves represent men and women from over sixty regiments, drawn to the cause from all corners of the Empire. They were wounded in battle or succumbed to disease, they were caught up in accidents or died at their own hands. These were soldiers of all ranks, age and class; brave pioneers of aviation; people seeking adventure on the high seas. Above all these were hopes, dreams and aspirations lost, cut tragically short for King and Country.

These were people like Guardsman Harold Dummett from the village of Kingsdon, who enlisted in the the Coldstream Guards, but died of pleurisy and pneumonia in 1919 at the age of just 19 years old.

These were soldiers like Rifleman Harry Trevetic of the King’s Royal Rifles. Born in Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire, he served in the Boer Wars and acted as batman to a Captain Makins.

Makins was injured on the Western Front, but Harry carried him to the nearest field hospital, then stayed with him there and returned to England as his assistant while he recovered.

Makins received his orders to return to the Front, but the idea of returning there horrified Rifleman Trevetic who chose to take his own life, rather than return to the terrors that awaited.

There was Second Lieutenant Sidney Pragnell from Sherborne in Dorset, who was so keen to play his part, he enlisted in the Royal Navy while under age.

He moved to the Royal Naval Air Service, which became the Royal Air Force, and was killed in a flying accident in August 1918.

Read more about Second Lieutenant Pragnell.

There was Staff Nurse Dorothy Stacey, also from Sherborne in Dorset who, because she came from a ‘good family’ was able to join the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserves.

After time spent tending to the troops returning wounded and injured from the Front, she fell ill, probably contracting one of the many conditions she had found herself treating, and died at the tender age of just 25 years old.

Read about Staff Nurse Stacey.

There was Private John Russell, who was hit by a motor car while guarding his camp. Just 19 years of age, he was buried in his home village of Meare, near Glastonbury.

The driver, Vera Coysh, went on to become an author of romantic novels.

Read more about Private Russell.

I am drawn to these sad and tragic tales, but also moved by the seeming randomness of the way life was taken.

The sleepy village of Lydeard St Lawrence has in its churchyard the graves of three brothers, William, Stephen and Ernest Rawle, all of whom died for their cause, leaving their other sibling, Edward, the only one to return from the European battlefields.

Read more about William Rawle, Stephen Rawle and Ernest Rawle.

In Yeovil Cemetery, on the other hand, lies Joseph Dodge, one of seven brothers to fight in the conflict, and the only one of the seven not to survive.

Read more about the life of Private Dodge.

There are countless stories to be told, and it is a privilege to be able to share some of these on the Death and Service website.